Author: Seema Rao

This month, inspired by the panel at Western Museums Association, we've been discussing all things audience, community, and visitors.

The far-ranging conversation in the second week (a summary of the panel) touched on how interconnected and slippery the terms we use about the people who enjoy our organizations (and for that matter the ones we wished did.)

For this week, I'm summarizing thoughts people had about community-engagement on Twitter. I asked the somewhat provocative question: Can museums go TOO far with audience engagement/ being visitor-centered?

Many people brought up the issue of defining terms, as I mentioned last week, including Linda Norris' comment:

Susan Spero added that community is a long-term investment. Their comments bring up the heterogeneity of the people associated with museums. There is a group of people who visit, but not all of them are invested in your organization. Similarly, there is a group of people don't visit, but they might be invested in your audience.Trying to think of a tweet-sized way to say..visitors, now, often are a not-so-diverse pool, some of whom are invested in your community & some who are not. But community members—your relationship w/ them will sustain (in every way) a museum if nurtured— Linda Norris (@lindabnorris) October 21, 2019

This issue is also linked to future growth. Membership programs are a good example. Most membership programs benefit people who already come or people just like them. They are a small, important sector of your organization. Yet, if CultureTrack's data is to be believed, membership as a funding model might be moving toward extinction. If you decide to plan future growth on the existing people walking in the door, you might be eschewing important audiences that would ensure a more stable future. Nina Simon pointed this out in a story about a museum with a cop in the lobby:

Museums often make poor choices for their visitors, current community, and future community when they don't really spend time understanding each group (and seeing the various nuances). I've always been fascinated about where museums think it's okay to get lax. Walk into any curatorial/exhibition meeting in a museum and say placard. I promise you at least three people will be unable to stop themselves from muttering "label." Knowledge is our core competency, on some level. Most museum professionals would never think to make something up about a collection object, but we are often, in essence, making things up about our visitors when we rely on anecdotal data. Any decision made on behalf of visitors bc I saw it once or my kid things or I believe is a poor one. Luis Marcelo Mendes brings up the hubris of museums in his humorous response:Members (mostly white families) said the cop’s presence made them feel safe. The museum wanted to engage more black families. Someone suggested they ditch the cop. They didn’t, for years. Their commitment (addiction?) to their existing visitors was too strong to shake loose.— Nina Simon (@ninaksimon) October 21, 2019

Regan Forrest's comments overlap both Nina's and Luis. Lack of knowledge can be incredibly problematic. When we make choices for the many, we are often doing so at the detriment of the few:Oh yeah, there’s always a chance that you want too much to love someone that doesn’t want to be loved, want to help someone that doesn’t need your help. Usually happens when museums KNOWS what a community need instead of asking them.— Luis Marcelo Mendes (@lumamendes) October 21, 2019

I've been thinking about this often in my work. Safe spaces, for example, is a phrase we use to imply a group of people may act without fear of their norms causing a stir. But who is safe if that space? Safety is often negotiated for the largest group, and so smaller groups safety can be compromised. Similarly, if visitor-centered is about the largest group, there are smaller groups who might suffer. This is not to say that visitor-centered means white-centered. But in keeping with Regan's point, if we don't question our premises and actively work to make visitor-centered diverse-focused, we might default to safe spaces/ visitor-centered spaces for whites/ majority groups.Lately I've been thinking about what being audience centred means when your audience is (or presumed to be) mostly white. Can attempts to be 'relevant' to the audience mean 'sanitising for white consumption' in some cases? If so, how do we address this?— Regan Forrest (@interactivate) October 20, 2019

And this is why clarity in terms of terms matters. When many museum professions say, this is just too visitor-centered, they are often highlighting their lack of knowledge, as Kate Livingston brought up:

In terms of the original question, for many people, it was about the line between visitors and curators. Nathan Lachenmeyer mentioned:The range of responses/reactions to your question shows varied understanding (or multiple definitions of) what audience engagement/visitor-centered *is*! This ‘semantics issue’ is, IMO, at the heart of how many decisions are ‘defended’ at museums. It can be problematic/cyclical.— Kate Livingston (also see @CoachKateLiv) (@exposyourmuseum) October 21, 2019

He went on to discuss how the museum should strive for a dialogue between what we want to share and what people want to know. (Something I agree with and wrote about previously.) Dean Krimmel suggested the guideline for too far was the mission. If you've picked up programs or exhibitions to draw visitors, but they don't connect to the mission you're on shaky ground. He mentioned the "so what" test, as a way to say, the mission and the ways we share the mission should be something that audiences want to know.I think that ideally a museum exhibition should be a dialog between the curator and the visitor. The content should inspire new questions, and answer some of them, and keep the audience engaged the whole time.— nathan lachenmyer (@morphogencc) October 20, 2019

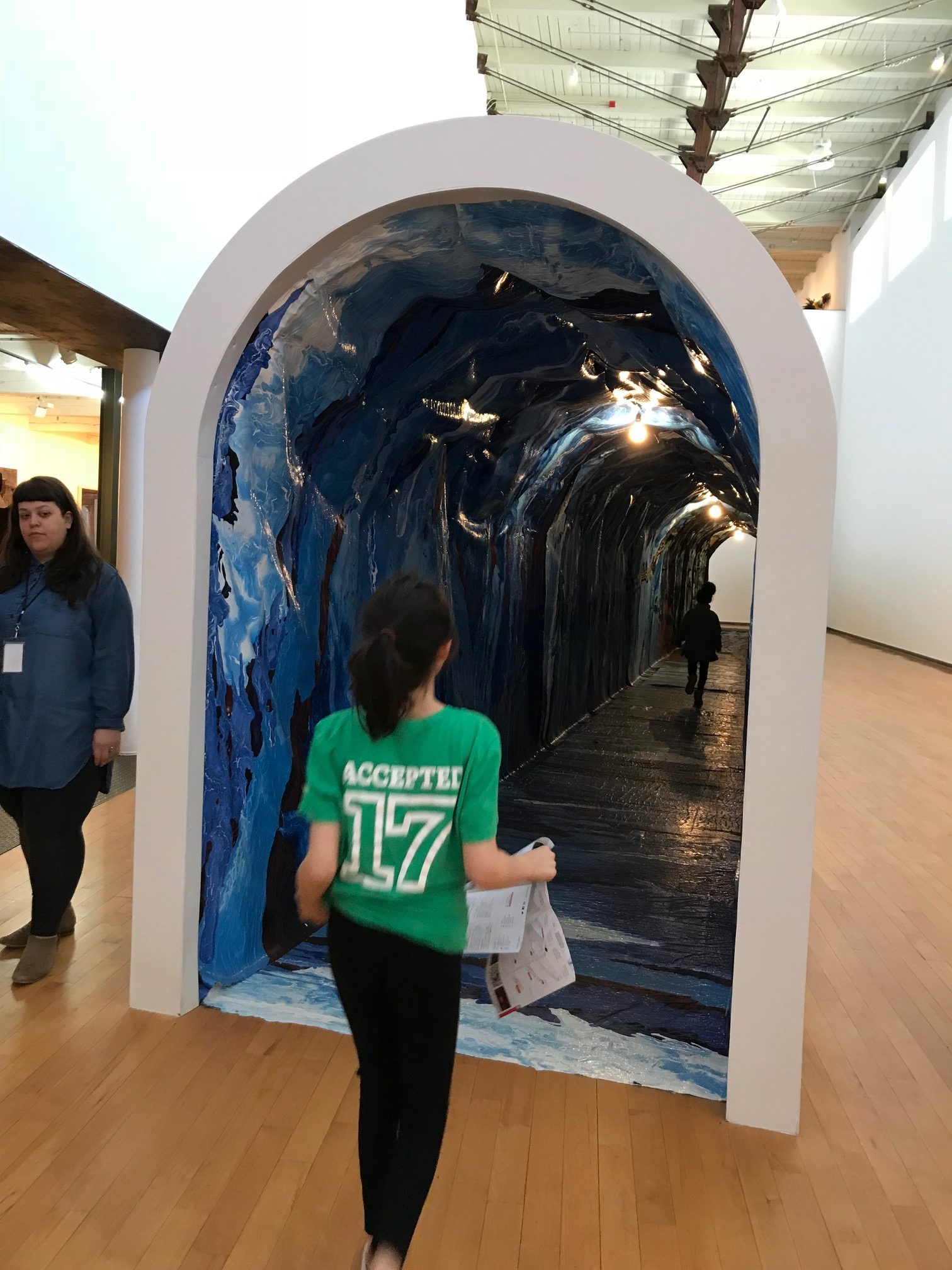

Many people saw Instagram museums as the ultimate non-mission driven, too far on the visitor-engagement. I might argue that their mission is to give people experiences, and they do well by their missions as their bank accounts show. And, understanding these orgs help museums, as Koven Smith brought up. It's important to interrogate what lines they've crossed and why. Those organizations are market-driven, as label me mabel PhD mentioned. To me, the biggest issue about those "museums" is that they are about now, the market today, not the future. That to me is what makes them different than traditional museums. We are not just about today but also in the future. When we let today's market drive our decisions, we are liable to lose future ones, as Nina mentioned above.

Right now, those, we still have a ways to go. We're not even close to being too visitor-centered; frankly many of us aren't even a little visitor-centered. As Jenny Lilac mentioned:

We've got a ways to go in understanding visitors, and I think also understanding ourselves. We need to consider the question of too visitor-centered in terms of not just the visitor but ourselves. When we say it's too visitor-centered, we might think the change is too far for us to brook. But then we need to be careful to go back to our mission. We are here for visitors. We are here to share, not hoard. As such, Matt might have asked the essential question for the monthThis is so hard to imagine. I can't say I've ever been to a museum and thought, "they have gone too far to try to engage me!" As long as museums are balancing preserving their collection for future generations, I don't think they can go to far.— jennylilac (@jennylilac) October 20, 2019

There will always be other things for people to do whether that's a bar, a movie, a football game, or a selfie stick theme park. What are we doing to give people a reason to choose us, and how do we make sure what we're doing is in line with our (aspirational) values?— Matt Popke 🎲 (@Polackio) October 21, 2019