Studying engineering taught me to think like a designer: state the problem, brainstorm, test, iterate.

Working with creative people taught me to think like an artist: observe, explore, dive in, look out.

Partnering in community taught me to think like an organizer: listen, connect, build shared purpose.

Building the Abbott Square project taught me a whole new mindset: that of the real estate developer.

Real estate developers have two distinctive qualities I’m learning to adopt: they think from the outside in, and they balance flexible optimism with clear criteria for success.

OUTSIDE IN

Before the Abbott Square project, I approached planning from an internally-driven perspective. We develop the ideas. We explore the possible programs. We develop the projects. The “we” isn’t always staff; in most cases, our staff work with community partners in a participatory, co-creative model. But we mostly start projects from the dreams and challenges of the partners in the room.

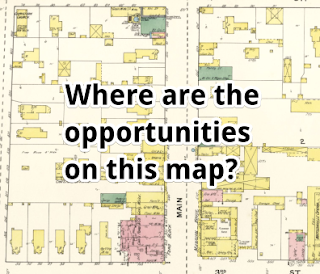

Real estate developers don’t think this way. They approach planning from the outside in, starting with the external conditions of the land around them. Each site provides its own set of opportunities and constraints. The question is not, “what do I want to do?” but “what can I do with this?”

This mindset expands my world. Even as we talk about “abundance thinking” in nonprofits, we tend to restrict ourselves to a limited landscape of opportunities. We don’t look too far beyond our existing programs, sites, and partners. We don’t scan every new encounter for its potential. Because we want control, we start by controlling ourselves, pre-selecting a narrow window of possibilities based on the frames we’ve already installed.

Real estate developers taught me to stop focusing on my own locus of control. Now I look outside the window and wonder what opportunities different sites and partners could unlock. It’s like Pokemon Go for professional opportunities; that site has some gold sparkles, that park is hopping with party animals, that collaboration request has a rainbow guarded by trolls.

FLEXIBLE OPTIMISM + HARD CRITERIA

Real estate developers blend optimism and flexibility with clear-eyed assessment of what external conditions make a project go. Developers will move mountains to make a project they believe in work—but they’ll also drop a project in an instant if the external conditions make it untenable. If a project doesn’t pencil out or meet the criteria they feel spell success, developers walk away. There will always be another site, another project, another opportunity for a better fit.

This approach requires being explicit and honest about criteria for success or failure. Every developer I’ve talked with can list specific things that will make them pursue or drop a project—at any stage. One guy will only work in specific municipalities. Another has to own the building. It doesn’t matter how attractive the project is if they can’t have what they feel they need to make it succeed.

In my nonprofit world, I’m neither required nor challenged to develop such clear criteria. My general nonprofit MO is to pursue a project and to keep adjusting and learning our way to the finish line. There are some projects that go on too long before they get axed. We identify flaws emergently rather than starting with clear “go/no go” criteria.”

Thinking like a developer has made me more comfortable pursuing many early-stage possibilities in parallel instead of marching forward in sequence. I assume most early-stage opportunities won’t end up lining up, but I won’t know which ones are viable until we get further down the road. I want the “deal flow” of opportunities—and I’m working to hone my own mental checklist of necessary criteria.

***

An artist says: “I’ll explore the world, pull ideas from it, and craft a response.”

A nonprofit manager says: “Based on what we’ve learned and the partnerships we’ve built, we’ll move forward like this, together.”

A developer says: “I’ll open many conversations, and when I find the one that meets all my criteria, I’ll go full steam ahead on that one and drop the others that don’t.”

All of these are valid ways to approach the world. Which will you use for your next project?

If you are reading this via email and would like to share a response or question, you can join the conversation here.