This summer, a gift landed in my podcast feed: a five-part series on evangelical church planting.

This podcast series didn't come from a Christian source. It came from Startup, a podcast about entrepreneurship. The series focuses on the intersection between mission and hustle--a battleground familiar to many nonprofit leaders.

I've been fascinated by church planting for a long time. Not because of religious affinity--I'm an atheist Jew--but because church planters teach me new lessons about relevance and inclusion.

Church planting is the act of creating new churches, often targeted for people who may not feel like church is relevant to them. Church plants bring the message of Christ to new people in new ways.

Like church planters, I'm passionate about connecting new people with mission-driven community experiences. I see church planting as way, way outside my comfort zone--leading to surprising, catalytic lessons.

Here are two reasons you might want to join me in learning from church planters:

1. Church plants are petri dishes of innovation when it comes to inviting new people into mission-based organizations.

Church plant pastors are a lot like other nonprofit leaders. They're passionate about organizational mission. They want to connect people to work they perceive as life-changing and sublime. But church planters pastors differ in an intriguing way: they are unapologetically evangelical. Their evangelism makes them creative, courageous hustlers when it comes to inviting new people into their work.

Some nonprofit leaders are put off by evangelism. It seems pushy, or gauche, to insist that passersby check out the art center or adopt environmental habits. We want people to be inspired by our mission... but we want them to come to it on their own. Instead of evangelizing, we hedge. We court newcomers, but not too much. If they don't come running to us, we demur. We don't want to be too exposed. We assume they just weren't interested. We drop it.

Evangelists don't hedge. They feel called to share the mission, to spread the message. They may be pushy, but they're also more whole-heartedly invested in bringing in newcomers. And that means they take bigger risks and attempt wilder experiments in making their work relevant.

Put in a daycare center? Hold services in a brew pub? Evangelists push themselves to reach new people in new ways. There's a lot we can learn from their experiments in pursuit of relevance.

2. Church plants are part of a healthy ecosystem for innovation and diversity--the kind of ecosystem I wish we had in the cultural sector.

The biggest, most established churches don't see church plants as threats. They see them as innovative feeders. Tim Keller, head of the giant Redeemer Presbyterian Church in NYC, claims that new churches are 3-6x better than established churches at attracting the "unchurched." And so Redeemer plants new churches. They don't just do it in far-flung cities. The majority of the churches they plant are in New York--the exact same city where Redeemer operates.

The result is an ecosystem in which large and established institutions help fuel new and risky ones. The rationale is both generous and self-serving. It's an abundance model, premised on the idea that more churches means more Christians and a better world for everyone. New churches bring new people to Christ. They bring new donors to Christ. And they bring fresh, innovative methods to pastors of churches old and new. So big churches like Redeemer spend time mentoring and funding church plants.

What would it look like if our largest organizations actively championed and funded new, experimental upstarts?

What would it feel like if we approached new potential audiences with the zeal of pastors on a mission?

What else can we learn from the weird and wonderful world of church planting?

Check out the podcast and let me know what you think.

Showing posts with label relevance. Show all posts

Showing posts with label relevance. Show all posts

Tuesday, August 28, 2018

Wednesday, June 08, 2016

The Art of Relevance Sneak Peek: What IS Relevance?

This month, I'm sharing a few chapters from my new book The Art of Relevance in advance of its release. I wrote this book because of a fundamental curiosity about what relevance is and how it works. Here's the second chapter of the book, which answers a basic question: what IS relevance? Who are the experts who study it, and how do they define it?

Note: this chapter is slightly edited to make sense in standalone form.

But if you’re like me, that definition is deeply unsatisfying. And the experts are on our side. Deirdre Wilson and Dan Sperber are cognitive scientists and leading theorists in the study of relevance. Their definition of relevance is more complex--and useful--than simply what’s hot.

Deirdre and Dan study how we transmit and receive information, mostly through speech. They argue that there are two criteria that make information relevant:

But if the movie is not showing nearby (high effort), or the reviews you read are conflicting and full of muddled information (negative cognitive effect), you’re stuck. You don’t get the useful conclusions you seek. It takes too much effort to find the right key to the door. You stay home.

Fulfilling these two criteria well can make a huge difference in how people respond to information. I saw this in 2015, when the World Health Organization released a study showing that processed meats—like bacon, ham, and sausages—are among the top five most cancerous products, alongside established killers like cigarettes and asbestos.

When I first saw this news, I was nonplussed. My husband and I are vegetarians, and for years, we’ve been reading studies like this. Top international health organizations have claimed for decades that a meat-free diet is vital to human health (not to mention reducing climate change impact). Period.

I assumed this 2015 study would have the same impact as all the others. Vegetarians and vegans would pass them around. We’d hesitantly foist them on our meat-eating friends and family members, expecting a mixture of disinterest, disbelief, and derision. And then everyone would go back to eating what they eat, believing what they believe.

But the 2015 study was different. It blew up on Facebook. It spawned thousands of news pieces, not just on health and foodie sites, but also on news outlets high and low. National papers. Business pages. Tech magazines. Op-eds. Blogs. I walked into the dentist’s office a week after the study came out, and the hygienist who cleaned my teeth told me the story had inspired her and her teenage son to stop eating meat. Here I’d spent years fumbling to get people who love me to even discuss the impact of eating meat, and one press release had motivated her family to give it up entirely.

I was blown away. How could one study—showing exactly what many other prominent studies have shown—have so much impact?

Consider the 2015 study in the context of relevance theory. The study linked two things that mattered to Americans in 2015: bacon and cancer. These are both emotionally-loaded topics. As a nation, we love bacon and eat it whenever we can. We hate cancer and avoid it however we can.

When a study links something we love to something we hate, it yields a conclusion that matters to us. The first criterion for relevance is satisfied. The research creates a surprising new connection between two things we care about. The mouthwatering sizzle of bacon on a pan. The pain we felt when our aunt went through chemo. It’s impossible not to experience a “cognitive effect” when reading about it—whether it yields a conclusion of distress, resolve to change, or somewhere in between. The effect may not be “positive” in how it feels, but it is “positive” in that it adds information to the decisions at hand.

You could argue that any study about the health impacts of food is relevant to all of us. After all, we all eat. But that relevance is only meaningful if it yields a conclusion that matters to you. And if bacon suddenly tastes like the pain of your aunt dying of cancer… that matters.

Throw cigarettes into the story and you satisfy the second criterion for relevance. This study’s conclusions were easy to understand. It took very little effort to connect the dots between our past experiences as a nation with cigarettes and new implications about bacon. Americans used to love cigarettes, until we discovered they cause cancer. Now, for the most part, we hate cigarettes. Does this mean we will one day feel about bacon the way we feel about cigarettes? Will little kids throw away their parents’ processed meat, crying that they don’t want to see Daddy die?

I hope so. But I suspect that the effort required to act on these conclusions will be too great for many bacon-lovers. There may be people like my dental hygienist out there, making a big effort based on the conclusions she has made. But there will be others who accept the information (the positive cognitive effect) but not the effort required to act.

If we want our work to be relevant, we need to satisfy both criteria. We need to provide a positive cognitive effect, and we need to make it possible with minimal effort. How likely is someone to derive a positive cognitive effect from visiting your site? How much effort will it require for them to do so? If it’s easy to visit, and the experience yields value, your work is bound to be relevant. But if it’s difficult to visit, and the value of the experience is hard to describe, why would anybody care to try?

Note: this chapter is slightly edited to make sense in standalone form.

Meaning, Effort, Bacon

In pop culture-land, relevance is all about now. Who's hot. What's trending.But if you’re like me, that definition is deeply unsatisfying. And the experts are on our side. Deirdre Wilson and Dan Sperber are cognitive scientists and leading theorists in the study of relevance. Their definition of relevance is more complex--and useful--than simply what’s hot.

Deirdre and Dan study how we transmit and receive information, mostly through speech. They argue that there are two criteria that make information relevant:

- How likely that new information is to stimulate a “positive cognitive effect”—to yield new conclusions that matter to you.

- How much effort is required to obtain and absorb that new information. The lower the effort, the higher the relevance.

But if the movie is not showing nearby (high effort), or the reviews you read are conflicting and full of muddled information (negative cognitive effect), you’re stuck. You don’t get the useful conclusions you seek. It takes too much effort to find the right key to the door. You stay home.

Fulfilling these two criteria well can make a huge difference in how people respond to information. I saw this in 2015, when the World Health Organization released a study showing that processed meats—like bacon, ham, and sausages—are among the top five most cancerous products, alongside established killers like cigarettes and asbestos.

When I first saw this news, I was nonplussed. My husband and I are vegetarians, and for years, we’ve been reading studies like this. Top international health organizations have claimed for decades that a meat-free diet is vital to human health (not to mention reducing climate change impact). Period.

I assumed this 2015 study would have the same impact as all the others. Vegetarians and vegans would pass them around. We’d hesitantly foist them on our meat-eating friends and family members, expecting a mixture of disinterest, disbelief, and derision. And then everyone would go back to eating what they eat, believing what they believe.

But the 2015 study was different. It blew up on Facebook. It spawned thousands of news pieces, not just on health and foodie sites, but also on news outlets high and low. National papers. Business pages. Tech magazines. Op-eds. Blogs. I walked into the dentist’s office a week after the study came out, and the hygienist who cleaned my teeth told me the story had inspired her and her teenage son to stop eating meat. Here I’d spent years fumbling to get people who love me to even discuss the impact of eating meat, and one press release had motivated her family to give it up entirely.

I was blown away. How could one study—showing exactly what many other prominent studies have shown—have so much impact?

Consider the 2015 study in the context of relevance theory. The study linked two things that mattered to Americans in 2015: bacon and cancer. These are both emotionally-loaded topics. As a nation, we love bacon and eat it whenever we can. We hate cancer and avoid it however we can.

When a study links something we love to something we hate, it yields a conclusion that matters to us. The first criterion for relevance is satisfied. The research creates a surprising new connection between two things we care about. The mouthwatering sizzle of bacon on a pan. The pain we felt when our aunt went through chemo. It’s impossible not to experience a “cognitive effect” when reading about it—whether it yields a conclusion of distress, resolve to change, or somewhere in between. The effect may not be “positive” in how it feels, but it is “positive” in that it adds information to the decisions at hand.

You could argue that any study about the health impacts of food is relevant to all of us. After all, we all eat. But that relevance is only meaningful if it yields a conclusion that matters to you. And if bacon suddenly tastes like the pain of your aunt dying of cancer… that matters.

Throw cigarettes into the story and you satisfy the second criterion for relevance. This study’s conclusions were easy to understand. It took very little effort to connect the dots between our past experiences as a nation with cigarettes and new implications about bacon. Americans used to love cigarettes, until we discovered they cause cancer. Now, for the most part, we hate cigarettes. Does this mean we will one day feel about bacon the way we feel about cigarettes? Will little kids throw away their parents’ processed meat, crying that they don’t want to see Daddy die?

I hope so. But I suspect that the effort required to act on these conclusions will be too great for many bacon-lovers. There may be people like my dental hygienist out there, making a big effort based on the conclusions she has made. But there will be others who accept the information (the positive cognitive effect) but not the effort required to act.

If we want our work to be relevant, we need to satisfy both criteria. We need to provide a positive cognitive effect, and we need to make it possible with minimal effort. How likely is someone to derive a positive cognitive effect from visiting your site? How much effort will it require for them to do so? If it’s easy to visit, and the experience yields value, your work is bound to be relevant. But if it’s difficult to visit, and the value of the experience is hard to describe, why would anybody care to try?

Labels:

Book: The Art of Relevance,

relevance

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

Advocacy Policy, Part Two - And Why Now is an Especially Good Time to Create One

Want to go straight to the policy?

Here it is.

Why create an advocacy policy?

In our case, it started when we were asked to sign onto a local petition to save a community garden under threat. We realized that we needed a systematic way to evaluate these kinds of requests--a tool that would help us evaluate when to say yes and why to say no.

Regardless of your institutional mission, nonprofits are all in the advocacy business. We champion causes through the partnerships we build, the programs we offer, and the stories we tell. While most nonprofits regularly advocate for our own institutions and/or sector, I think it's just as important to advocate for the interests of the communities in which we serve.

If you've been considering this for awhile, now is the time to act. Everyone is going to the ballot this year in the United States. Our museum has already had several requests to lend our support to bond measures that will be on the ballot in 2016. While 501c3 nonprofits cannot endorse candidates, it is completely kosher to endorse bond measures, propositions, and other ballot measures. If you want to be engaged in 2016 ballot measures relevant to your institution or community, now is a great time to develop a policy for how and when to do so.

How did we create it?

A small team of trustees and staff members worked together on our advocacy policy. We reviewed a handful of existing policies from other institutions (local and national, museums and not), discussed their attributes, and started drafting/stealing/reworking with a Google doc. We only met once in person. It was especially valuable to have activists, retired government employees, and social service leaders on the team; they brought helpful perspectives on what advocacy means beyond a cultural context.

The policy our board approved is intentionally broad. We wanted enough of a foundation to ground our advocacy without prescribing it. We wanted enough of a process to provide clarity and structure without too many hoops. We wanted it to make "yes" possible but "no" completely reasonable as well.

Any surprises?

One of the biggest "aha" moments I had in the development of the policy is that our museum was already doing advocacy in a variety of ways before we had a policy. We educate the public on local issues. We invite people from community organizations and campaigns to use the museum as a platform to share their message. We partner with thousands of artists and organizations, providing staff support and engagement in their work. We incubate a youth art and social change program. We host community festivals like the recent Artivism event that showcase local changemakers. We've made changes to our museum--bilingual signage, all-gender restrooms--to be better advocates for the diverse visitors who walk through our doors.

Though we started working on the policy specifically to address situations when we are asked by an outside group for formal endorsement, we realized as we dove in that we should also use this opportunity to contextualize endorsements as just one of many advocacy tools at our disposal. Advocacy is not just for executives and boards of trustees. The result is a broad policy that empowers our whole team to think about our roles as advocates for our community in the work we do.

I know our policy is not perfect. We're just starting to use it to evaluate endorsement requests coming our way, and I imagine we'll find some ways we want to clarify or change what we've written. But I wanted to share it with you: in appreciation of your role in its development, in curiosity as to your response, and in hopes it might inspire you to draft your own.

Because no matter the content, I heartily advocate for such policies to exist.

If you are reading this via email and would like to share a comment or question, you can join the conversation here.

Labels:

inclusion,

relevance,

social justice

Wednesday, December 02, 2015

A Different Story of Thanksgiving: The Repatriation Journey of Glenbow Museum and the Blackfoot Nations

I spent last week holed up in a cabin, working on my forthcoming book, The Art of Relevance. One of the most powerful books I read while doing research was We are Coming Home: Repatriation and the Restoration of Blackfoot Cultural Confidence (read it free here, great appreciation to Bob Janes for sharing it with us). The book is a deep account of repatriation of spiritual objects from museums to native people, written by museum people and Blackfoot people together. I hope this synopsis might inspire you to read their full incredible story.

How do institutions build deep relationships with community partners? What does it look like when institutions change to become relevant to the needs of their communities--and vice versa?

Going deep is a process of institutional change, individual growth, and most of all, empathy. It requires all parties to commit. Institutional leaders have to be willing and able to reshape their traditions and practices. Community participants have to have to be willing to learn and change too. And everyone has to build new bridges together.

That’s what happened when the Blackfoot people and the Glenbow Museum worked together over the course of twenty years to repatriate sacred medicine bundles from the museum to the Blackfoot.

This story starts in 1960s, though of course, the story of the Blackfoot people and their dealings with museums started way before that. Blackfoot people are from four First Nations: Siksika, Kainai, Apatohsipiikani, and Ammskaapipiikani (Piikani). Together, the four nations call themselves the Niitsitapi, the Real People. The Blackfoot mostly live in what is now the province of Alberta, where the Glenbow Museum resides.

Like many ethnographic museums around the world, Glenbow holds a large number of artifacts in its collection that had belonged to native people. Many of the most holy objects in its collection were medicine bundles of the Blackfoot people.

A medicine bundle is a collection of sacred objects—mostly natural items—securely wrapped together. Traditionally, museums saw the bundles as important artifacts for researchers and the province, helping preserve and tell stories of the First Nations. Museums believed they held the bundles legally, purchased through documented sales. By protecting the bundles, museums were protecting important cultural heritage for generations to come. Many museums respected the bundles’ spiritual power by not putting them on public display. They made the bundles available for native people to visit, occasionally to borrow. But not to keep.

The Blackfoot people saw it differently. For the Blackfoot, these bundles were sacred living beings, not objects. They had been passed down from the gods for use in rituals and ceremonies. Their use, and their transfer among families, was an essential part of community life and connection with the gods. The bundles were not objects that could be owned. They were sacred beings, held in trust by different keepers over time. If they had been sold to museums, those sales were not spiritually valid. They were not for sale or purchase by any human or institution.

Why had the objects been sold in the first place? Many medicine bundles had been sold to museums in the mid-1900s, when Blackfoot ceremonial practices were dying out. The 1960s were a low point in Blackfoot ceremonial participation. Ceremonial practices had ceased to be relevant to most Blackfoot people, due in large part to a century-long campaign by the Canadian government to “reeducate” native people out of their traditions. Blackfoot people are as subject to societally-conferred notions of value as anyone else. In the 1960s, when Blackfoot culture was dying, some bundle keepers may have seen the bundles as more relevant as source of money for food than as sacred beings. Others may have sold their bundles to museums hoping the museums would keep them through the dark days, holding them safe until Blackfoot culture thrived again.

By the late 1970s, that time had come. Blackfoot people were eager to reclaim their culture. They were ready to use and share the bundles once more. The museums were not. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Blackfoot leaders attempted to repatriate medicine bundles back to their communities from various museums. Some tried to negotiate. Others tried to take bundles by force. In all cases, they ran into walls. While some museum professionals sympathized with the desires of the Blackfoot, they did not feel that those desires outweighed the legal authority and common good argument for keeping the sacred bundles. Museums held a firm line that they were preserving these objects for all humanity, which outweighed the claim of any particular group.

In 1988, the Glenbow Museum wandered into the fray. They mounted an exhibition, “The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples,” that sparked native public protests. The exhibition included a sacred Mohawk mask which Mohawk representatives requested be removed from display because of its spiritual significance. More broadly, native people criticized the exhibition for presenting their culture without consulting them or inviting them into the process. The museum had broken the cardinal rule of self-determination: nothing about us, without us.

A year later, a new CEO, Bob Janes, came to Glenbow. Bob led a strategic planning process that articulated a deepened commitment to native people as “key players” in the development of projects related to their history and material culture. In 1990, Bob hired a new curator of ethnology, Gerry Conaty. That same year, Glenbow made its first loan of a medicine bundle--the Thunder Medicine Pipe Bundle--to the Blackfoot people.

The loan worked like this: the Weasel Moccasin family kept the Thunder Medicine Pipe Bundle for four months to use during ceremonies. They, they returned the bundle to the museum for four months. This cycle was to continue for as long as both parties agreed. This was a loan, not a transfer of ownership. There was no formal protocol or procedure behind it. It was the beginning of an experiment. It was the beginning of building relationships of mutual trust and respect.

In the 1990s, curator Gerry Conaty spent a great deal of time with Blackfoot people, in their communities. He was humbled and honored to participate as a guest in Blackfoot spiritual ceremonies. The more Gerry got to know leaders in the Blackfoot community, people like Daniel Weasel Moccasin and Jerry Potts and Allan Pard, the more he learned about the role of medicine bundles and other sacred objects in the Blackfoot community.

Gerry started to experience cognitive dissonance and a kind of dual consciousness of the bundles. As a curator, he was overwhelmed and uncomfortable when he saw people dancing with the bundles, using them in ways that his training taught him might damage them. But as a guest of the Blackfoot, he saw the bundles come alive during these ceremonies. He saw people welcome them home like long-lost relatives. He started to see the bundles differently. The Blackfoot reality of the bundles as living sacred beings began to become his reality.

Over time, Gerry and Bob became convinced that full repatriation—not loans—was the right path forward. The bundles had sacred lives that could not be contained. They belonged with the Blackfoot people.

But the conviction to change was just the beginning of the repatriation process. The institution had to change long-held perceptions of what the bundles were, who they belonged to, and how and why they should be used. This was a broad institutional learning effort, what we might call "cultural competency" today. During the 1990s, Glenbow started engaging Blackfoot people as advisors on projects. Gerry hired Blackfoot people wherever he could, as full participants in the curatorial team. Bob, Gerry, and Glenbow staff spent time in Blackfoot communities, learning what was important and relevant to them.

As Blackfoot elders sought to repatriate their bundles from museums, they also had to negotiate amongst themselves to reestablish the relevance and value of the bundles. They were relearning their own ceremonial rituals and the role of medicine bundles within them. They had to develop protocols for how they would adopt, revive, and recirculate the bundles in the community. Even core principles like the communal ownership of the bundles had to be reestablished. This process took just as much reshaping for Blackfoot communities as it did for the institution.

To complicate things further, the artifacts were actually the property of the province of Alberta, not Glenbow. The museum couldn’t repatriate the bundles without government signoff. For years they fought to get government approval. For years, the government resisted. Government officials suggested that the Blackfoot people make replicas of the bundles, so the originals could remain "safe" at the museum. The museum and their Blackfoot partners said no. As Piikani leader Jerry Potts put it: “Well, who is alive now who can put the right spirit into new bundles and make them the way they are supposed to be? Who is there alive who can do that? Some of these bundles are thousands of years old, and they go right back to the story of Creation when Thunder gave us the ceremony. Who is around who can sit there and say they can do that?”

The museum and Blackfoot leaders had to negotiate multiple realities. They had to negotiate on the province’s terms through legal battles and written contracts. They had to negotiate with museum staff about policies around collections ownership and management. They had to negotiate with native families about the use and transfer of the bundles in the community. In each arena, different approaches and styles were required. The people in the middle had to navigate them all.

But they kept building momentum through shared learning and loan projects. By 1998, the Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani had more than thirty sacred objects on loan from the Glenbow Museum. They were still fighting for the province to grant the possibility of full repatriation. Still, even as loans, some bundles had been ceremonially transferred several times throughout native communities, spreading knowledge and extending relationships. Glenbow staff had learned the importance of the bundles to entire communities. Native people were using, and protecting, and sharing the bundles. Even the Glenbow board bought in. The museum had become relevant to the native people on their terms. The native people had become relevant to the museum on theirs. They were more than relevant; they were connected, working together on a project of shared passion and commitment.

In 1999, they put their shared commitment to the test. It became clear that they were not going to succeed at convincing the provincial cultural officials of the value of full repatriation. CEO Bob Janes went to the Glenbow board of trustees and told them about the stalemate. A board member brokered a meeting with the premier of Alberta so that the museum could make the case for repatriation directly. It was risky; they were flagrantly ignoring the chain of provincial command. But the gamble worked. In 2000, the First Nations Sacred Ceremonial Objects Repatriation Act was passed in the province of Alberta. The bundles went home.

At its heart, the story of the Blackfoot repatriation is the story of two communities—that of the Blackfoot and that of Glenbow Museum—becoming deeply relevant to each other. When relevance goes deep, it doesn’t look like relevance anymore. It looks like work. It looks like friendships. It looks like shared meaning. As the museum staff understand more about what mattered to their Blackfoot partners, it came to matter to them, too. Leonard Bastien, then chief of the Piikani First Nation, put it this way: “Because all things possess a soul and can, therefore, communicate with your soul, I am inclined to believe that the souls of the many sacred articles and bundles within the Glenbow Museum touched Robert Janes and Gerry Conaty in a special way, whether they knew it or not. They have been changed in profound ways through their interactions with the Blood and Peigan people and their attendance at ceremonies.”

That is the power of deep relevance.

If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment below. If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

How do institutions build deep relationships with community partners? What does it look like when institutions change to become relevant to the needs of their communities--and vice versa?

Going deep is a process of institutional change, individual growth, and most of all, empathy. It requires all parties to commit. Institutional leaders have to be willing and able to reshape their traditions and practices. Community participants have to have to be willing to learn and change too. And everyone has to build new bridges together.

That’s what happened when the Blackfoot people and the Glenbow Museum worked together over the course of twenty years to repatriate sacred medicine bundles from the museum to the Blackfoot.

This story starts in 1960s, though of course, the story of the Blackfoot people and their dealings with museums started way before that. Blackfoot people are from four First Nations: Siksika, Kainai, Apatohsipiikani, and Ammskaapipiikani (Piikani). Together, the four nations call themselves the Niitsitapi, the Real People. The Blackfoot mostly live in what is now the province of Alberta, where the Glenbow Museum resides.

Like many ethnographic museums around the world, Glenbow holds a large number of artifacts in its collection that had belonged to native people. Many of the most holy objects in its collection were medicine bundles of the Blackfoot people.

A medicine bundle is a collection of sacred objects—mostly natural items—securely wrapped together. Traditionally, museums saw the bundles as important artifacts for researchers and the province, helping preserve and tell stories of the First Nations. Museums believed they held the bundles legally, purchased through documented sales. By protecting the bundles, museums were protecting important cultural heritage for generations to come. Many museums respected the bundles’ spiritual power by not putting them on public display. They made the bundles available for native people to visit, occasionally to borrow. But not to keep.

The Blackfoot people saw it differently. For the Blackfoot, these bundles were sacred living beings, not objects. They had been passed down from the gods for use in rituals and ceremonies. Their use, and their transfer among families, was an essential part of community life and connection with the gods. The bundles were not objects that could be owned. They were sacred beings, held in trust by different keepers over time. If they had been sold to museums, those sales were not spiritually valid. They were not for sale or purchase by any human or institution.

Why had the objects been sold in the first place? Many medicine bundles had been sold to museums in the mid-1900s, when Blackfoot ceremonial practices were dying out. The 1960s were a low point in Blackfoot ceremonial participation. Ceremonial practices had ceased to be relevant to most Blackfoot people, due in large part to a century-long campaign by the Canadian government to “reeducate” native people out of their traditions. Blackfoot people are as subject to societally-conferred notions of value as anyone else. In the 1960s, when Blackfoot culture was dying, some bundle keepers may have seen the bundles as more relevant as source of money for food than as sacred beings. Others may have sold their bundles to museums hoping the museums would keep them through the dark days, holding them safe until Blackfoot culture thrived again.

By the late 1970s, that time had come. Blackfoot people were eager to reclaim their culture. They were ready to use and share the bundles once more. The museums were not. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Blackfoot leaders attempted to repatriate medicine bundles back to their communities from various museums. Some tried to negotiate. Others tried to take bundles by force. In all cases, they ran into walls. While some museum professionals sympathized with the desires of the Blackfoot, they did not feel that those desires outweighed the legal authority and common good argument for keeping the sacred bundles. Museums held a firm line that they were preserving these objects for all humanity, which outweighed the claim of any particular group.

In 1988, the Glenbow Museum wandered into the fray. They mounted an exhibition, “The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples,” that sparked native public protests. The exhibition included a sacred Mohawk mask which Mohawk representatives requested be removed from display because of its spiritual significance. More broadly, native people criticized the exhibition for presenting their culture without consulting them or inviting them into the process. The museum had broken the cardinal rule of self-determination: nothing about us, without us.

A year later, a new CEO, Bob Janes, came to Glenbow. Bob led a strategic planning process that articulated a deepened commitment to native people as “key players” in the development of projects related to their history and material culture. In 1990, Bob hired a new curator of ethnology, Gerry Conaty. That same year, Glenbow made its first loan of a medicine bundle--the Thunder Medicine Pipe Bundle--to the Blackfoot people.

The loan worked like this: the Weasel Moccasin family kept the Thunder Medicine Pipe Bundle for four months to use during ceremonies. They, they returned the bundle to the museum for four months. This cycle was to continue for as long as both parties agreed. This was a loan, not a transfer of ownership. There was no formal protocol or procedure behind it. It was the beginning of an experiment. It was the beginning of building relationships of mutual trust and respect.

In the 1990s, curator Gerry Conaty spent a great deal of time with Blackfoot people, in their communities. He was humbled and honored to participate as a guest in Blackfoot spiritual ceremonies. The more Gerry got to know leaders in the Blackfoot community, people like Daniel Weasel Moccasin and Jerry Potts and Allan Pard, the more he learned about the role of medicine bundles and other sacred objects in the Blackfoot community.

Gerry started to experience cognitive dissonance and a kind of dual consciousness of the bundles. As a curator, he was overwhelmed and uncomfortable when he saw people dancing with the bundles, using them in ways that his training taught him might damage them. But as a guest of the Blackfoot, he saw the bundles come alive during these ceremonies. He saw people welcome them home like long-lost relatives. He started to see the bundles differently. The Blackfoot reality of the bundles as living sacred beings began to become his reality.

Over time, Gerry and Bob became convinced that full repatriation—not loans—was the right path forward. The bundles had sacred lives that could not be contained. They belonged with the Blackfoot people.

But the conviction to change was just the beginning of the repatriation process. The institution had to change long-held perceptions of what the bundles were, who they belonged to, and how and why they should be used. This was a broad institutional learning effort, what we might call "cultural competency" today. During the 1990s, Glenbow started engaging Blackfoot people as advisors on projects. Gerry hired Blackfoot people wherever he could, as full participants in the curatorial team. Bob, Gerry, and Glenbow staff spent time in Blackfoot communities, learning what was important and relevant to them.

As Blackfoot elders sought to repatriate their bundles from museums, they also had to negotiate amongst themselves to reestablish the relevance and value of the bundles. They were relearning their own ceremonial rituals and the role of medicine bundles within them. They had to develop protocols for how they would adopt, revive, and recirculate the bundles in the community. Even core principles like the communal ownership of the bundles had to be reestablished. This process took just as much reshaping for Blackfoot communities as it did for the institution.

To complicate things further, the artifacts were actually the property of the province of Alberta, not Glenbow. The museum couldn’t repatriate the bundles without government signoff. For years they fought to get government approval. For years, the government resisted. Government officials suggested that the Blackfoot people make replicas of the bundles, so the originals could remain "safe" at the museum. The museum and their Blackfoot partners said no. As Piikani leader Jerry Potts put it: “Well, who is alive now who can put the right spirit into new bundles and make them the way they are supposed to be? Who is there alive who can do that? Some of these bundles are thousands of years old, and they go right back to the story of Creation when Thunder gave us the ceremony. Who is around who can sit there and say they can do that?”

The museum and Blackfoot leaders had to negotiate multiple realities. They had to negotiate on the province’s terms through legal battles and written contracts. They had to negotiate with museum staff about policies around collections ownership and management. They had to negotiate with native families about the use and transfer of the bundles in the community. In each arena, different approaches and styles were required. The people in the middle had to navigate them all.

But they kept building momentum through shared learning and loan projects. By 1998, the Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani had more than thirty sacred objects on loan from the Glenbow Museum. They were still fighting for the province to grant the possibility of full repatriation. Still, even as loans, some bundles had been ceremonially transferred several times throughout native communities, spreading knowledge and extending relationships. Glenbow staff had learned the importance of the bundles to entire communities. Native people were using, and protecting, and sharing the bundles. Even the Glenbow board bought in. The museum had become relevant to the native people on their terms. The native people had become relevant to the museum on theirs. They were more than relevant; they were connected, working together on a project of shared passion and commitment.

In 1999, they put their shared commitment to the test. It became clear that they were not going to succeed at convincing the provincial cultural officials of the value of full repatriation. CEO Bob Janes went to the Glenbow board of trustees and told them about the stalemate. A board member brokered a meeting with the premier of Alberta so that the museum could make the case for repatriation directly. It was risky; they were flagrantly ignoring the chain of provincial command. But the gamble worked. In 2000, the First Nations Sacred Ceremonial Objects Repatriation Act was passed in the province of Alberta. The bundles went home.

At its heart, the story of the Blackfoot repatriation is the story of two communities—that of the Blackfoot and that of Glenbow Museum—becoming deeply relevant to each other. When relevance goes deep, it doesn’t look like relevance anymore. It looks like work. It looks like friendships. It looks like shared meaning. As the museum staff understand more about what mattered to their Blackfoot partners, it came to matter to them, too. Leonard Bastien, then chief of the Piikani First Nation, put it this way: “Because all things possess a soul and can, therefore, communicate with your soul, I am inclined to believe that the souls of the many sacred articles and bundles within the Glenbow Museum touched Robert Janes and Gerry Conaty in a special way, whether they knew it or not. They have been changed in profound ways through their interactions with the Blood and Peigan people and their attendance at ceremonies.”

That is the power of deep relevance.

If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment below. If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

Monday, November 16, 2015

OdysseyWorks: An Empathy-Based Approach to Making Art

The quest for relevance begins with knowing your audience. Who are the people with whom you want to connect? What are their dreams, their impressions, their turn-offs, their fears?

The quest for relevance begins with knowing your audience. Who are the people with whom you want to connect? What are their dreams, their impressions, their turn-offs, their fears?Ultimately, any approach to answering these questions is limited at some point by the size of the audience involved. When you are dealing with an audience of hundreds or thousands of people, you have to make assumptions. You have to generalize.

But what if you only had an audience of one?

OdysseyWorks is a collective that makes immersive art experiences for one person at a time. They select their audience--by application or commission--and then they spend months getting to know that person. They spend time with them. They call references. They try to understand not just the surface of the individual's personality but the fundamental way that person sees the world. And then, based on their research, they remake the world for a weekend, twisting the person's environment with sensory experiences that explore and challenge their deepest inclinations.

When I first heard about OdysseyWorks, I thought their projects were indulgent novelties. But the more I learned, the more I appreciated their thoughtful slanted window into audience engagement.

OdysseyWorks' projects get to the heart of the fiercest debates in the arts today. Does "starting from the audience" mean pandering to narcissism and dumbing down work? Is it elitist to present art that may be dislocating or foreign? How do we honor the audience's starting point and take them somewhere new?

As artistic director Abe Burickson described their work to me, I imagined Theseus walking deeper into the labyrinth towards the Minotaur. Theseus entered the labyrinth with a string tying him to what he already knew. And then he followed that string into darkness, danger, and ultimately, triumph.

I asked Abe about how he sees the tension between the desire to start with the audience and the desire to move the audience somewhere new. He spoke of the audience as providing a challenge, a challenge like any other artistic constraint. The audience provides an offering of a certain way of looking, a challenge to see the world differently and get inside that perspective with their artwork. OdysseyWorks locates that starting point, hands the audience the string, and draws them further and deeper into mystery.

Abe told me about a performance OdysseyWorks created for a woman named Christina. Christina loved all things symmetrical and tonal. Loved baroque and rococo. Hated Jackson Pollock and John Cage. The OdysseyWorks team is not that way - they like messy and atonal - so it was an interesting challenge. Could they create a space of comfort, a world of her own, and then move her to a space of dischord where the things OdysseyWorks thought were beautiful might become beautiful to her?

Here's how Abe described the project to me:

We started the weekend in Christina's comfort zone. We started with Clair de Lune by Debussy, which she loves, and a few other structured things that worked that way. Over time, she encountered the music in multiple locations--in a symmetrical architectural space, with family.

As the day went on, she relaxed--which is key to the process. When you engage with something, especially something new, you are often on guard, physically, socially, intellectually. You just don’t trust right away.

When you no longer feel that people are judging you, you become much more open to new things. It's really quite amazing how much of a shift can happen.

Once those reservations and judgments faded, we started playing other version of Clair de Lune. There are hundreds of really messed up versions of Clair de Lune. We played them just to shake it up. At one point after seven hours, and about 500 miles of travel, Christina got picked up by a train and was driven to a scene. It was about an hour drive. And in that hour, she just listened to this Clair de Lune version we composed, this 80-minute deconstruction, a slow deterioration, that started classical and ended sounding like people chewing on string. It was beautiful noise. It was the exact opposite of what she liked, and yet by that point, she found it beautiful.

The whole experience was kind of a deconstruction of form. The experience was powerful for her. Later she said it pried her open.

The goal was not that Christina should like John Cage. Nor is it about creating a moment of pleasure. The goal was to create work that is moving for her and a compelling artistic challenge for us. It's about creating a different engagement with life.To me, the biggest aha this story is the middle--the enormous role that the perception of "being judged" plays in narrowing our experience and our openness to new things. When we trust, we open up. But how often does an arts institution start working with an audience by building a trusting relationship (versus bombarding them with content)? What could we gain by starting with empathy instead of presentation?

OdysseyWorks is doing a crowd-funding campaign right now to fund a book project documenting their process. I'm learning from them, so I'm supporting them. Check out their work and consider whether they might help you through the labyrinths in your world.

If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment below. If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

Wednesday, November 04, 2015

Women of Color Leading Essential, Activist Work in Cultural Institutions

| A new poster from the National Park Service, based on Rich Black's 2009 image. |

Here are three sources that have inspired me, from four activist women of color. Each of these women push the boundaries of cultural institutions in different ways, with digital and physical manifestations. But don't take my word for it. These women all have strong online presences, and I invite you to join me in learning from and supporting their work.

Ravon Ruffin and Amanda Figuero - Claiming Space for Brown Women in the Digital Museum Landscape

Based in Washington DC, Brown Girls Museum Blog is a new-ish site led by graduate students Ravon Ruffin and Amanda Figueroa. Ravon and Amanda are using several social media channels to explore and share museum exhibitions, programs, and projects. They are holding meetups, creating swag, and getting heard. Ravon spoke at MuseumNext last month (video here) about how communities of color claim space and power in the decentralized digital landscape. I was impressed by her expertise, and the example that Raven and Amanda are setting in strengthening their own voices as emerging leaders in this space. I can't wait to see what happens as they claim more space and power in museums, both through this project and individually in their careers.

Monica Montgomery - Building a Museum of Impact

In New York City, Monica Octavia Montgomery is pushing the boundaries of how we make relevant, powerful museum exhibits with the Museum of Impact. The Museum of Impact is a pop-up project of short-term exhibitions on urgent topics of social justice. Monica is a museum pioneer in two ways: she is using the museum medium to tackle tough social issues, and she is inventing new models for urgent, responsive, relevant programming. Monica publicly launched Museum of Impact this year with an exhibition on #blacklivesmatter, and she has projects on other themes--immigration, environment, mass incarceration--in the works. Want to know more? Check out this great interview with Monica by Elise Granata, and learn more about how you can get involved.

Betty Reid Soskin - Rewriting History in the National Parks

Yes, I DID save the best for last. Betty Reid Soskin is a nationally-renowned park ranger in Richmond, CA, and I am completely blown away by what I've learned from her in the short few weeks since I first heard her name. Betty is the oldest national park ranger in America at 94, but more importantly, Betty is an activist, a truth-seeker, and a storyteller. She speaks, writes, and fights for justice--in a federal historic site.

Betty gives tours at the Rosie the Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park, sharing her lived experience working there as a clerk during the war. Her blog, CBreaux Speaks, is one of the most eloquent I've ever read. She writes about race, history, parks, culture, and politics. She writes with power, and a voice unlike any I've encountered online. And she's been blogging for over 12 years.

Here's an excerpt from one of Betty Reid Soskin's earliest blog posts, from September 2003, when she was first asked to participate in the planning of the national park in which she now works. She was in the room as an elder, a civic leader, and a part of the site's history. But she immediately saw that she had an additional role to play: as a truth-teller of the full history of the site. Here's how she described it:

In the new plan before us, the planning team was taken on a bus tour of the buildings that will be restored as elements in the park. They're on scattered sites throughout the western part of the city. One of two housing complexes that has been preserved, Atchison and Nystrom Villages. They consist of modest bungalows, mostly duplexes and triplexes that were constructed "for white workers only." In many cases, the descendants of those workers still inhabit those homes. They're now historic landmarks and are on the national registry as such.

Since we're "telling the story of America through structures," how in the world do we tell this one? And in looking around the room, I realized that it was only a question for me. It held no meaning for anyone else.

No one in the room realizes that the story of Rosie the Riveter is a white woman's story. I, and women of color will not be represented by this park as proposed. Many of the sites names in the legislation I remember as places of racial segregation -- and as such -- they may be enshrined by a generation that has forgotten that history.

There is no way to explain the continuing presence of the 40% African American presence in this city's population without including their role in World War II. There continues to be a custodial attitude toward this segment of the population, with outsiders unaware of the miracle of those folks who dropped their hoes and picked up welding torches to help to save the world from the enemy. Even their grandchildren have lost the sense of mission and worthiness without those markers of achievement and "membership" in the effort to save the world.

And, yes, I did tell them. And, I have no idea what they'll do with the information, but I did feel a sense of having communicated those thoughts effectively to well-meaning professionals who didn't know what in hell to do the information.Fortunately, Betty Reid Soskind did a heck of a lot more than participating in that 2003 planning session. She became a leader in the development, and now the interpretation, of Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park.

Spend time on Betty's blog, and get inspired by her journey as an activist and a truth-teller, a passionate advocate for what cultural institutions can do to advance truth and justice for all. Support Ravon and Amanda and Monica, and their journeys to become leaders in our field. Our cultural universe is full of stars. When we deny ourselves the full brilliance of the stories and voices in that universe, we impoverish our own experiences. We cloud the potential for truth, beauty, and justice.

Let us all be amateur astronomers of culture, huddled around the powerful telescopes of diverse experience. Let us seek truth, beauty, and justice, and amplify them, together.

Labels:

cultural competency,

inclusion,

institutional change,

relevance,

web2.0

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Seeking Your Stories of Relevance and Irrelevance for a New Book Project

Dear Museum 2.0 friends,

Dear Museum 2.0 friends,I know I that I haven't been sharing a lot on the blog, but behind the scenes, you've inspired me to write more than ever. Energized by the response to the blog series this summer on relevance, I've decided to write a book on the topic. My goal is to make it short, the focus tight, and release it quickly: hopefully spring 2016.

The book will roughly cover:

- what relevance is, why it matters, and when it doesn't

- relevance to WHO - identifying and making legitimate connections with communities of interest

- relevance to WHAT - making confident connections to mission, content, and form

- relevance as a GATEWAY to deep experiences vs. relevance as a PROCESS of deepening involvement

- measuring relevance

- irrelevance - its dangers and distractions

My goal is for this book to be relevant to anyone on a mission to matter more. That's where you come in. I'm in research mode, and I'm seeking stories and case studies from diverse institutions about attempts, successes, failures, and discoveries related to relevance. I'm specifically seeking stories from:

- science institutions

- media organizations

- institutions that focus on a specific cultural/ethnic group

- religious institutions

- historical societies

- theater

- dance

- parks

- libraries

- organizations outside the US

- anyone willing to share an honest story related to irrelevance

You can share a short anecdote or a detailed case study--I'm looking for sources at all levels at this point. THANK YOU in advance for helping make this book as relevant and compelling as possible (and yes, I think those two terms are quite different and am writing about the difference in the book).

If you have a story, or know someone with a story, please leave a comment here or send me an email. If you are reading this via email and wish to leave a comment, you can join the conversation here.

Labels:

relevance

Wednesday, September 02, 2015

Meditations on Relevance Part 5: Relevance is a Bridge

|

| Blessing of the Replica Boards, July 19, 2015, 8am. Photo by Jon Bailiff. |

But a bridge to nowhere is quickly abandoned. Relevance only leads to deep meaning if it leads to something significant. Killer content. Substantive programming. Muscle and bone.

This summer, we opened two exhibitions at my museum that are highly relevant to local culture. One is about the Grateful Dead (Dear Jerry), the other about the dawn of surfing in the Americas (Princes of Surf). Dear Jerry is relevant because Santa Cruz is a hippie town, UC Santa Cruz maintains the Grateful Dead Archive, and the Dead did their final tour this summer. Princes of Surf is about the young Hawaiian princes who brought surfing to the Americas 130 years ago--relevant because they did it in Santa Cruz, with boards shaped from local wood, on waves I bike by every week.

Both of these exhibitions are relevant to the cultural identity of Santa Cruz. Both had good design, great programmatic events, and enthusiastic response. But one of them--Princes of Surf--completely outshone the other. Crushed attendance records. Yielded mountains of press. Captured people like we've never seen before. Princes of Surf isn't "more relevant" than Dear Jerry. But its gateway led further into our community, deeper into the heart-spirit of Santa Cruz.

What makes Princes of Surf so special? The exhibition is small and fairly traditional in design. It features only two artifacts: the original redwood surfboards the princes shaped and used in Santa Cruz. Picture a room with two really long pieces of old wood, and some labels around the walls. That's about it.

And yet. These two pieces of wood are like the Shroud of Turin of surfing in the Americas. They are the answer to a mystery, proof of something we'd long believed but couldn't verify. They are at the heart of how so many people in my community define themselves. These boards connect modern-day surfers to something greater than themselves: across oceans, across cultures, across time. It's not about nostalgia. It's about a new connection to something deep inside.

Princes of Surf is simple. It starts with a theme--surfing--that is relevant to our community. And then it delivers something new and shocking, something old and reverent, something worth getting excited about.

The story of how these surfboards became significant speaks to the fickle face of relevance. Before the Princes of Surf exhibition, these boards rested deep in the collection storage of the Bishop Museum in Hawaii. As royal boards, they were sufficiently relevant to the Bishop's mission to be collected--but not compelling enough to warrant exhibition. They were in storage for 90+ years before historians in Hawaii and Santa Cruz discovered they were THE boards in the first known record of surfing in the Americas in Santa Cruz. The boards became relevant and important in Santa Cruz, and we paid a huge amount to have them conserved and shipped here for exhibition. But their significance here doesn't translate across the ocean. After this "blockbuster" run in Santa Cruz, the boards will go back in storage at the Bishop Museum, where their relevance warrants preservation but little adoration.

In other words, these boards are significant--but only here, only because of their relevance to Santa Cruz. Attributes like "significance" are almost always contextual. And potent. When context and meaning line up, objects gain power.

Exhibiting these boards reminds me how rare it is to exhibit truly significant objects. So often in museums, we assuage ourselves with the idea that in the digital era, people will still visit museums because they want to see "the real thing." What we don't admit is that many of the "real things" we display just aren't compelling enough to get people in the door. We lie to ourselves, writing shiny press releases for exhibitions of second-class objects and secondhand stories. The rechewed meat of culture. The thin, oily soup of blockbuster shows. They may be relevant, but that doesn't make them valuable.

I remember the last time I saw an object that was so relevant, and so valuable, that it had huge community impact. It was June of 2009. Michael Jackson had just died, and I was at the Experience Music Project in Seattle, where they hastily erected an exhibit of the jacket and glove he wore in the Thriller video. Many organizations hosted tributes to Michael Jackson, but this tribute, this artifact, this outfit that froze Michael Jackson at his most insane and fabulous and other-worldly--it mattered. It was relevant AND significant.

When you hit both these notes, people respond. With Princes of Surf, it started before the exhibition opened. People lining the street on the Tuesday afternoon when the boards arrived from the Port of Oakland, cheering as the crates came off the truck. People pouring in to see the show. Grown men fighting for seats at lectures about the history of the boards. Couples stopping me on the street to marvel about the story. Kids wearing commemorative t-shirts around town. The exhibition is still open, and every week I have these moments--in the museum and out in the City--where people tell us and show us how much the boards matter to them.

My favorite moment of this project was on July 19, 2015, 130 years to the day since the teenage Hawaiian princes were first documented surfing on mainland USA in Santa Cruz. We celebrated the anniversary with a surf demo, paddle out, and luau. One of the most prominent surfboard designers in Santa Cruz, Bob Pearson of Pearson Arrow, shaped fourteen replica redwood boards for the demo. We partnered with pro surfers, shapers, surf historians, Hawaiian restaurants, a local radio DJ, and a Hawaiian biker club to make it happen.

It's always nerve-wracking when you host an event with an unconventional format. I remember early morning on July 19, getting on my bike, wondering if anyone would be at the beach when I arrived. Who in their right minds would show up at 8am on a Sunday for a history event?

I arrived to a sea of people, heads bent before a blessing of the boards. I stumbled into the throng. Someone handed me a lei. I walked with hundreds of fellow Santa Cruzans along the shoreline to watch pro surfers attempt to ride the replicas. People lined the cliffs above the water. The tide was low, and we walked way out along the break, cheering the surfers on, watching them rise and fall.

Back on the beach, the mayor proclaimed it Three Princes Day. The Hawaiian motorcycle club hefted the 200+ pound replicas and carried them down the shore to the rivermouth where the princes first surfed, like a reverse funeral for history being raised from the dead. A the mouth of the river where the princes rode, Hawaiian elders led us in a song of blessing. And then we got into the water again - hundreds of us, on redwood boards and longboards and shortboards and paddle boards and no boards at all, paddling out to form a circle in the ocean out beyond the break, holding hands, feeling the connection. We paddled back, dried off, and spent the afternoon drinking beer and dancing hula in the courtyard outside the museum.

So let's celebrate relevance. Not as an end, but as a means. If your organization focuses on your local geography, be relevant to that. If you focus on a particular community, be relevant to them. If you focus on a discipline or art form or niche, be relevant to that. And then work like hell to make meaning out of it.

Because relevance is just a start. It is a bridge. You've got to get people on the bridge. But what matters most is what they're moving towards, on the other side.

***

This essay is part of a series of meditations on relevance. Thank you for taking this journey with me. It is an experiment in form, and I value all the comments and conversation around it. If there are other topics you think should be included in the series, please leave a comment with that topic for consideration.

Here's my question for today: Have you seen an object or work of art become relevant and powerful for a short time or in a particular context? How do you define the difference between relevance and significance?

If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment or send me an email with your thoughts. If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

Labels:

exhibition,

Museum of Art and History,

relevance

Wednesday, August 26, 2015

Meditations on Relevance, Part 4: Guest Comic and Open Thread

For the past few weeks, I've been writing about relevance and museums. The conversation in the comments on each post has been fascinating and educational. Today, I wanted to share a provocative comic made by a talented museum-er/illustrator, Crista Alejandre. I hope this piece encourages more dialogue among us in this penultimate post in the relevance series.

This post is part of a series of meditations on relevance. This week is YOUR WEEK to weigh in on anything related to relevance that you want to explore. At the end of the series, I'll re-edit the whole thread into a long format essay. I look forward to your examples, amplifications, and disagreements shaping the story ahead.

Here's my question for you today: What responses, questions, and stories does Crista's comic spark for you?

If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

***

This post is part of a series of meditations on relevance. This week is YOUR WEEK to weigh in on anything related to relevance that you want to explore. At the end of the series, I'll re-edit the whole thread into a long format essay. I look forward to your examples, amplifications, and disagreements shaping the story ahead.

Here's my question for you today: What responses, questions, and stories does Crista's comic spark for you?

If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

Wednesday, August 19, 2015

Meditations on Relevance, Part 3: Who Decides What's Relevant?

One of my favorite comments on the first post in this series came from Lyndall Linaker, an Australian museum worker, who asked:

"Who decides what is relevant? The curatorial team or a multidisciplinary team who have the audience in mind when decisions are made about the best way to connect visitors to the collection?"

One of my favorite comments on the first post in this series came from Lyndall Linaker, an Australian museum worker, who asked:

"Who decides what is relevant? The curatorial team or a multidisciplinary team who have the audience in mind when decisions are made about the best way to connect visitors to the collection?"My answer: neither. The market decides what's relevant. Whoever your community is, they decide. They decide with their feet, attention, dollars, and participation.

When you say you want to be relevant, that usually means "we want to matter to more people." Or different people. Can you define the community to whom you want to be relevant? Can you describe them? Mattering more to them starts with understanding them. What they care about. What is useful to them. What is on their minds.

The community decides what is relevant to them. But who decides what is relevant inside the organization? Who interprets the interests of the community and decides on the relevant themes and activities for the year?

That's a more complicated question. It's a question of HOW we decide, not just WHO makes the decision.

Community First Program Design

At the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, we've gravitated towards a "community first" program planning model. It's pretty simple. Instead of designing programming and then seeking out audiences for it, we identify communities and then develop programs that are relevant to their assets and needs.

Here's how we do it:

- Define the community or communities to whom you wish to be relevant. The more specific the definition, the better.

- Find representatives of this community--staff, volunteers, visitors, trusted partners--and learn more about their experiences. If you don't know many people in this community, this is a red flag moment. Don't assume that content/form that is relevant to you or your existing audiences will be relevant to people from other backgrounds.

- Spend more time in the community to whom you wish to be relevant. Get to know their dreams, points of pride, and fears.

- Develop collaborations and programs, keeping in mind what you have learned.

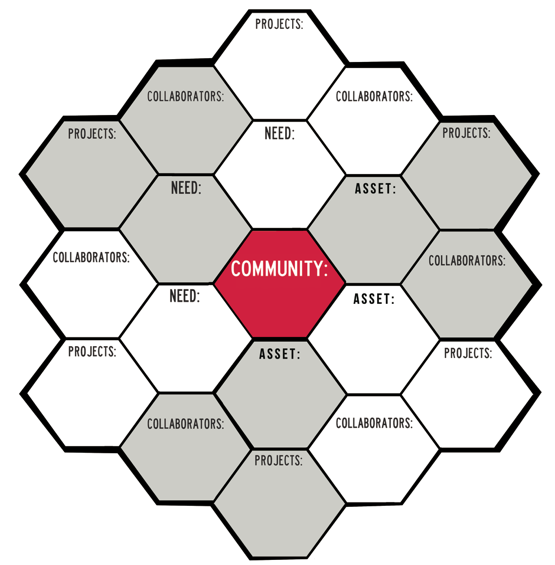

We use a simple "honeycomb" diagram (image) to do these four steps.

We use a simple "honeycomb" diagram (image) to do these four steps.We start at the middle of the diagram, defining the community of interest.

Then, we define the needs and assets of that community. We're careful to focus on needs AND assets. Often, organizations adopt a service model that is strictly needs-based. The theory goes: you have needs; we have programs to address them. While needs are important, this service model can be demeaning and disempowering. It implies we have all the answers. It's more powerful to root programming in the strengths of a community than its weaknesses.

Once we've identified assets and needs, we seek out collaborators and project ideas. We never start with the project idea and parachute in. We start with the community and build to projects.

Here are two examples:

- Our Youth Programs Manager, Emily Hope Dobkin, wanted to find a way to support teens at the museum. Emily started by honing in on local teens' assets: creativity, activist energy, desire to make a difference, desire to be heard, free time in the afternoon. She surveyed existing local programs. The most successful programs fostered youth empowerment and community leadership in various content areas: agriculture, technology, healing. But there was no such program focused on the arts. Subjects to Change was born. Subjects to Change puts teens in the driver's seat and gives them real responsibility and creative leadership opportunities at our museum and in collaborations across the County. Subjects to Change isn't rooted in our collection, exhibitions, or existing museum programs. It's rooted in the assets and needs of creative teens in our County. Two years after its founding, Subjects to Change is blasting forward. Committed teens lead the program and use it as a platform to host cultural events and creative projects for hundreds of their peers across the County. The program works because it is teen-centered, not museum-centered.

- Across our museum, we're making efforts to deeply engage Latino families. One community of interest are Oaxacan culture-bearers in the nearby Live Oak neighborhood. There is a strong community of Oaxacan artists, dancers, and musicians in Live Oak. One of their greatest assets is the annual Guelaguetza festival, which brings together thousands of people for a celebration of Oaxacan food, music, and dance. Our Director of Community Engagement, Stacey Marie Garcia, reached out to the people who run the festival, hoping we might be able to build a collaboration. We discovered--together--that each of us had assets that served the other. They had music and dance but no hands-on art activities; we brought the hands-on art experience to their festival. They have a strong Oaxacan and Latino following; we have a strong white following. We built a partnership in which we each presented at each other's events, linking our different programming strengths and audiences. No money changed hands. It was all about us amplifying each other's assets and helping meet each other's needs.

Getting New Voices in Your Head

The essential first step to this "community first" process is identifying communities of interest and learning about their assets, needs, and interests.

How does this critical learning happen? There are many ways to approach it. You can form a community advisory group. A focus group. Recruit new volunteers or board members. Hire new staff. Volunteer in that community. Seek out trusted leaders and make them your partners. Seek out community events and get involved.

We find that the more time we spend in communities of interest--hiring staff from those communities, recruiting volunteers from those communities, helping out in those communities, and collaborating with leaders in those communities--the easier it is to make reasonable judgments about what is and isn't relevant. It gets easier to hear their voices in our heads when we make a decision. To imagine what they'll reject and what they'll embrace.

If you want to make program decisions relevant to a group, the thing you need most is their voices in your head. Not your voice. Not the voices of existing participants who are NOT from the community of interest.

Here's the challenge: if this community of interest is new to you, it's hard to get their voices in your head. It's hard for two reasons:

- If you are interested in being relevant to a community that is new to you, you likely have low familiarity and knowledge of that community's assets, needs, and interests.

- At the same time as you are learning about this community, stumbling into new conversations, your existing community is right there, loud and in your face, drowning out the new voices you are seeking in the dark.

It's easy to give up. It's easy to just listen to the voices already in front of you. To stay relevant to them and shed your visions of being relevant to more or different people.

But you can't give up. If you believe in the work of being relevant to new communities, you have to believe those people are out there. You have to privilege their voices in your head. You have to believe that their assets and needs and dreams are just as valid as those of people who are already engaged.

Every time an existing patron expresses concern about a change, you have to imagine the voices in your head of those potential new patrons who will be elated and engaged by the change. You have to hear their voices loud and clear.

These new voices don't exist yet. They are whispers from the future. But put your ear to the ground, press forward in investing in community relevance, and those whispers will be roars before you know it.

***

This essay is part of a series of meditations on relevance. If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment or send me an email with your thoughts. At the end of the series, I'll re-edit the whole thread into a long format essay. I look forward to your examples, amplifications, and disagreements shaping the story ahead.

Here's my question for you today: Who decides what is relevant in your institution? Have you ever seen a project succeed or fail based on interpretation of community assets and needs?

If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

Labels:

inclusion,

institutional change,

relevance,

visitors

Tuesday, August 04, 2015

Meditations on Relevance, Part 2: Content vs. Form

In pop culture-land, relevance is all about now. Who's hot. What's trending. If people on the street are talking about X, the museum should be talking about X too.

This is the least useful form of relevance for the arts. "Now" is not an easy business model to chase--especially for institutions rooted in permanence. "Now" requires major changes to how we work and what we offer. "Now" comes off as disingenuous and irrelevant if done wrong. And now is not tomorrow. It is not the long term. It is just now. Endlessly, persistently, expensively, now.

I used to work at The Tech Museum of Innovation in San Jose, CA. Our mandate was to be the museum of Silicon Valley--not of its material history, but its pulse of innovation. This was impossible. The exhibits we put on the floor were immediately dated. Their physicality, long timelines, and big budgets made them immutable objects. They didn't speak to the thrilling drumbeat of change at the heart of innovation.

The problem was not one of content but one of form. This isn't just a science center problem. It's a cultural institution problem. The solution is in focusing on changing form more than content. Changing hours and pricing. Curatorial processes. Interpretative techniques.

Consider the experiments at the New World Symphony in Miami, where they are performing classical orchestral music for outdoor "wallcasts" that include projections and visual content. Or Streb Labs, where choreographer Elizabeth Streb flipped the traditional dance model by opening a 24/7, open-access venue for practice and performance. Or museums that extend their hours to match working people's schedules.