Showing posts with label relationships. Show all posts

Showing posts with label relationships. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 10, 2019

Hello Museum World!

Hello World! Or maybe hello museum world! I feel a bit like a child walking around in someone else’s, slightly bigger shoes taking over this wonderful blog. The metaphor certainly works in terms of filling big shoes. But, I like that metaphor for another reason. Children see play and imagination as their job. Filling big shoes isn’t scary; it’s something to enjoy and pursue with zeal. I am taking this challenge in that way—a wonderful, playful exploration. I hope you join me on this romp (and pick me up if I wobble). This month, I wanted to share some stories from my last two years as a strategy and content consultant. (Previously, I had worked at the same museum for 17 years.) I went from lots of change in one place to help many places with their change. And, while over the next few months, I'll share things about me, I wanted to write today about the field.

So, when you visit more than 300 museums, parks, and historic sites, what do you learn? I thought I would kick off my tenure around here by sharing stories and reflections about my visits. This week, I wanted to start with us, museum and cultural workers. In these last two years, I have spoken to hundreds of colleagues around the world, both in person and on social. I’ve learned so much from all of you, and a little about us as a field. Here are my top five reflections:

1. We Care: I know this might seem obvious, but it is worth calling this out. We are a field of people who truly care about our work. We are not in this for the 9-5, and most of us work well beyond the average work week. This is a hard point to illustrate with a story because every story I will share for the next few weeks is about the care we put into the work. Each label, I assure you, is a testament to the care of scores of museum workers. Each time a front walk is plowed in the snow, each time someone helps a visitor find their way to a gallery, each time you see a funny social media post. The care we put into our work is the fabric of this field. It makes me immensely proud to be one of you at every one of my visits.

2. Front of House is Hard Work: While I did gallery teaching for many years, for most of my career, I’ve had a desk and a phone in non-public space. A portion of our sector lives their work lives in the public realm. These front of house workers, including visitor experience staff and security guards, are often the ones taking our missions to the people.

I was so impressed by the front of house workers. On a very hot day last month, I tromped into the Dyckman Farm House in Manhattan, glistening from the heat and the trek, to see a smiling gardener invite me to sit down in the shade. Another time, I walked into MASS MOCA with my two elementary-age daughters. A guard knelt down to tell my daughters there were some interesting works in this gallery that could be touched (and he pointed out everything else is look only). He spoke to them as humans (not with a baby voice), and he seemed like he was happy to see us. I attempted to do some of the interactives in the National Museum of Scotland with wonderful encouragement from the education staff there. Let’s just say my pedal power is not so powerful, but I felt supported and encouraged. Overall, our front of house workers very often put our field’s best face forward.

3. Some of Our Staff are Listening: It’s hard to remember a time before Museum 2.0, and Nina’s advocacy for interactivity in our gallery spaces. So many museums have taken up the charge to make their spaces engaging on different levels. And while interactivity is up in general, I was particularly impressed by the number of museums who are proactive about visitor feedback and prototyping.

I saw places where museums were being transparent about how they do their work. My favorite, perhaps, was the prototype space at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle. As they were readying for a huge revamp of their spaces, they turned a gallery into a prototype space. My favorite little section was a place where people could vote on the styles of labels. My children particularly loved watching a technician/ scientist work on processing an avian taxidermy sample. Different strokes, perhaps. But, both of these sections were drawing back the curtain, if you will, on the work of museums. I wholeheartedly believe museums seem more vital to visitors when they know we are a changing, evolving field. When we show we are growing, we invite people to see our changes.

4. Some of our Staff still Needs to Listen: As a field, we still have so much growth. Take labels, for example. Many of our labels seem like the text that time forgot. They are written for a populace that is largely non-existent, people without Google on their phones and infinite attention spans. Now, I say this as someone who has written scores of labels and taught others to write them. I have definitely written some poor labels in my life. (And I will be writing much more deeply about labels in an upcoming post).

But for the sake of this list, I use labels as an example of a place where we as a field have not done a good job of evolving. There is nothing in our work that is so sacred as to be above scrutiny. Being critical of every element of our work, and every expectation, can only improve our practices.

5. Our Staff is Taxed: I wrote a book ages ago now about Self-Care. It started as an act of self-care myself. I was tired intellectually, and I needed to find a better way of being in this field. I was so glad other people liked the book. But, in writing that book, I also found people came to me about their problems. I was happy to listen (still am), but I realized something was fundamentally wrong in our field. My book was an individual helping other individuals. Certainly, caring for yourself is important.

But I think we as a field need to think about why so many of our professionals are feeling taxed. As I said above, our visitors might not see this exhaustion when they walk in. But burnout leads to job turnover. Losing trained people is like throwing away money. I don’t have the answer, but I have been trying to find systemic ways to embed wellness into the ways we run our museums.

In conclusion for this week, we are doing good work--you are doing good work. It can be hard, and often underappreciated, but it makes a difference. Next week, I'll talk about my reflections on how visitors seem to feel in our galleries.

N.B. In an upcoming post, I'd love to think about guards. If you have been a guard, ever, consider taking this survey. I'll make anonymized data available to anyone who asks.

I'll be checking comments, obviously. But, I'm easy to find on social @artlust on twitter and @_art_lust_ on IG.

Labels:

design,

evaluation,

exhibition,

relationships,

visitors

Thursday, December 07, 2017

Guest Post by Jasper Visser: Storytelling for Social Cohesion at Story House Belvédère

I first read about Story House Belvédère on Jasper Visser’s excellent blog, The Museum of the Future. This small, startup cultural project in Rotterdam works directly and intimately with community members to share their stories. It is a platform for social bridging and cultural exchange. Jasper enhanced his original post to share with you here. I hope you’ll be as charmed and inspired by Story House Belvédère as I am.

Story House Belvédère in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is a magical place. On a beautiful location in a former jazz-era night club, a committed team works on storytelling activities to bring different communities in the city together, and contribute to a happier, more engaged city. They do so by making the stories of individuals and communities visible, and encouraging new encounters. In its short existence (it opened in 2013), the place has made a name for itself as a successful community-driven, innovative cultural initiative.

I visited Story House Belvédère as part of the new Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museum Projects I am involved in. I had heard a lot about Belvédère before my visit, so my expectations were high. The place surpassed them. I spoke with some of the people working there, especially founder Linda Malherbe.

What makes Story House Belvédère so special?

It is rooted in its diverse neighborhood and the people who live there.

Story House Belvédère is in Katendrecht, in southern Rotterdam. Katendrecht is a part of town that for over 125 years has been a home for migrants and newcomers to the city. The neighborhood is a mix of people and communities by design and has a rich social history. Currently, the neighborhood is being gentrified and its development, which tells a wider story about the city, is ongoing. The team found the current home of Belvédère almost by chance when they were looking for a temporary working space. But the location proved perfect. According to Linda, the project could not have been imagined and developed anywhere else in the city. A diversity of people and stories is the reason it exists.

It started as a community project rooted in relationship-building.

Before there was a house, the team behind Belvédère organised a community-focused social photography exhibition outdoors on one of the quais in the south of Rotterdam. It was an exhibition of group portraits of the many communities in the area. City officials doubted the idea of an exhibition in the public space in a part of town they considered dangerous. They said, "you will get shot at, and in two weeks everything will be destroyed." But they were wrong. The exhibition was up for a year and a half. When it ended, the portrayed communities took their portraits home, starting relationships with Belvédère which in some cases still persist.

After the photography show, the team was encouraged to continue their work. They focused on one of the key events in Rotterdam history: the bombing of the city at the beginning of the Second World War. Inspired by Story Corps, they toured the neighborhood with a mobile recording studio and captured memories of the bombing. They created storytelling events and shows, which prompted other communities to start telling their own stories. As Linda says, “Every story inspires a new story.”

The success of the storytelling events encouraged the team to look for a permanent location. They found it in the old jazz club/boxing gym/neighborhood museum Belvédère, a building which dates back to 1894. Together with the communities they had worked with before, they are now renovating the building. In 2018 it will officially reopen. But currently you can visit when the door is unlocked - which is almost daily. After the formal reopening, they still expect to evolve. As Linda says, the process will never be finished, as people will always continue to add and make changes to the building to reflect new stories and ideas.

The community values of the team permeate the space and their projects.

Already you can feel Story House Belvédère is a special place. You feel it the moment you step into their warm and welcoming space. It feels like a living room, where everybody can be a friend. Even the coffee cups and the cookies are in style. The magic, of course, goes beyond aesthetics and is deeply embedded in the organization.

A small team is the driving force behind all projects. It is a committed, dynamic group of freelancers who care about the mission and magic of the place. The place they created is warm and welcoming, and yet it is their energy and enthusiasm that stuck with me most after my visit. I asked Linda to describe what defines the team, and received over a dozen characteristics:

This approach permeates all activities of Story House Belvédère. If you rent the place for a private event such as a wedding, some spots at the event are reserved for people from other communities. So, if you’re interested in joining a Syrian wedding or Jewish Bar Mitzvah, you can. The reason this works is because of the personal ties between the team and the communities. The aim of Linda and her team is to create relationships with people that are everlasting.

Story House Belvédère in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is a magical place. On a beautiful location in a former jazz-era night club, a committed team works on storytelling activities to bring different communities in the city together, and contribute to a happier, more engaged city. They do so by making the stories of individuals and communities visible, and encouraging new encounters. In its short existence (it opened in 2013), the place has made a name for itself as a successful community-driven, innovative cultural initiative.

I visited Story House Belvédère as part of the new Intangible Cultural Heritage and Museum Projects I am involved in. I had heard a lot about Belvédère before my visit, so my expectations were high. The place surpassed them. I spoke with some of the people working there, especially founder Linda Malherbe.

What makes Story House Belvédère so special?

It is rooted in its diverse neighborhood and the people who live there.

Story House Belvédère is in Katendrecht, in southern Rotterdam. Katendrecht is a part of town that for over 125 years has been a home for migrants and newcomers to the city. The neighborhood is a mix of people and communities by design and has a rich social history. Currently, the neighborhood is being gentrified and its development, which tells a wider story about the city, is ongoing. The team found the current home of Belvédère almost by chance when they were looking for a temporary working space. But the location proved perfect. According to Linda, the project could not have been imagined and developed anywhere else in the city. A diversity of people and stories is the reason it exists.

It started as a community project rooted in relationship-building.

Before there was a house, the team behind Belvédère organised a community-focused social photography exhibition outdoors on one of the quais in the south of Rotterdam. It was an exhibition of group portraits of the many communities in the area. City officials doubted the idea of an exhibition in the public space in a part of town they considered dangerous. They said, "you will get shot at, and in two weeks everything will be destroyed." But they were wrong. The exhibition was up for a year and a half. When it ended, the portrayed communities took their portraits home, starting relationships with Belvédère which in some cases still persist.

After the photography show, the team was encouraged to continue their work. They focused on one of the key events in Rotterdam history: the bombing of the city at the beginning of the Second World War. Inspired by Story Corps, they toured the neighborhood with a mobile recording studio and captured memories of the bombing. They created storytelling events and shows, which prompted other communities to start telling their own stories. As Linda says, “Every story inspires a new story.”

The success of the storytelling events encouraged the team to look for a permanent location. They found it in the old jazz club/boxing gym/neighborhood museum Belvédère, a building which dates back to 1894. Together with the communities they had worked with before, they are now renovating the building. In 2018 it will officially reopen. But currently you can visit when the door is unlocked - which is almost daily. After the formal reopening, they still expect to evolve. As Linda says, the process will never be finished, as people will always continue to add and make changes to the building to reflect new stories and ideas.

The community values of the team permeate the space and their projects.

Already you can feel Story House Belvédère is a special place. You feel it the moment you step into their warm and welcoming space. It feels like a living room, where everybody can be a friend. Even the coffee cups and the cookies are in style. The magic, of course, goes beyond aesthetics and is deeply embedded in the organization.

A small team is the driving force behind all projects. It is a committed, dynamic group of freelancers who care about the mission and magic of the place. The place they created is warm and welcoming, and yet it is their energy and enthusiasm that stuck with me most after my visit. I asked Linda to describe what defines the team, and received over a dozen characteristics:

- A shared love for people

- They are good listeners

- Positively curious, and always asking new questions

- Actively looking for (a diversity of) people

- Etc. etc.

This approach permeates all activities of Story House Belvédère. If you rent the place for a private event such as a wedding, some spots at the event are reserved for people from other communities. So, if you’re interested in joining a Syrian wedding or Jewish Bar Mitzvah, you can. The reason this works is because of the personal ties between the team and the communities. The aim of Linda and her team is to create relationships with people that are everlasting.

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

Platform Power: Scaling Impact

Last month, I sat in the back of a meeting room at the MAH and watched something extraordinary happen. Our county board of supervisors had brought their official meeting to the museum. They were off-site for the first time in years, holding a special study session sparked by an exhibition about foster youth, Lost Childhoods. The supervisors toured the exhibition with some of the 100+ local partners who helped create it. Then, for an hour, former foster youth who helped design the exhibition shared their stories with supervisors. They spoke powerfully and painfully about their experiences. They shared their hopes. They urged the politicians to fix a broken system. It felt like something opened up, right in that room, between the flag and the tissues and the microphones. It felt like change was breaking through.

This was not an event orchestrated by the MAH. It happened because two of our Lost Childhood partners urged it into being. They negotiated with the County. They set the table. They made something real and meaningful happen.

They did it because the exhibition belonged to them. They helped conceive it, plan it, and build it. The Lost Childhoods exhibition is a platform for 100+ partners to share their stories, artwork, ideas, projects, volunteer opportunities, and events.

Nine years ago, I wrote a post called The Future of Authority: Platform Power. In it, I argued that museums could give up control of the visitor experience while still maintaining (a new kind of) power. Museums could make the platforms for those experiences. There is power IN the platform--power to shape the way people participate. This argument became one of the foundations of The Participatory Museum.

Nine years later, I still believe this. Now that I run a museum, I experience the variety of ways we can create platforms that empower community members to do certain things, in certain ways, that amplify the institution. The power IN the platform is real. But I've also become reenergized about the power OF the platform for those community members who participate. I value platforms for their power to scale impact.

Traditionally, museums and cultural organizations offer programs. Staff produce them for, and sometimes with, visitors. Each program has a fixed cost, and expanding that program means expanding that cost. If it takes a staff member 5 hours to run a screen-printing workshop, it takes her ten hours to run it twice. Even a smash hit program is hard to scale up in this model.

At the MAH, we've tried wherever possible to break out of unidirectional program models. We believe that we can most effectively empower and bridge community members (our strategic goal) if we invite them to share their skills with each other. This is the participatory platform model. Instead of staff running workshops, our staff connect with local printmaking collectives. We ask them what their goals are for outreach and community connection. And then we support and empower them to lead workshops and festivals and projects on our site. Instead of "doing the thing" directly, our staff make space for community members to do the thing--and to do so beautifully, proudly, with and for diverse audiences.

Does this work scale better than programs? It's not always obvious from the start whether it will. This work is relationship-heavy, and those relationships take time to build. When we created an exhibition with 100 community members impacted by the foster care system, it took almost a year to recruit, convene, open up, explore, and create the products and the trust to build those products well. But that investment in building a platform paid off.

When you build relationships in a platform, you build participants' power. Platforms can accommodate lots of partners and support them taking the projects in new directions. Since opening in July, exhibition partners haven't just planned a County supervisors' meeting. They've led over 50 exhibition-related community events at and beyond the MAH. They've created powerful learning experiences, diverse audiences, and new program formats. Our staff could never produce all this activity on our own. We put our energy into empowering partners, which ignited their passion and ability to extend the exhibition to new people and places.

Whereas a program is a closed system, a platform is an open one. In a platform model, more is not more staff time and cost. More is more use of the platform, more participants empowered to use it to full potential.

As our organization grows, we are looking for more ways to adopt a platform mindset. Now that we've opened Abbott Square, we have a goal to offer free cultural programming almost every day of the week. This means a huge shift for the MAH (previously we offered 2 monthly festivals plus a few scattered events). How will we increase our event offerings so aggressively? We're not planning to do it by adding a lot of staff to programming the space. We're planning to do it by building new platforms. We are learning from our "monthly festival" platform and building a lightweight, more flexible version. We want to make it easier for community groups to plug in, offering their own workshops and festivals and events, with our support. If we can create the right platform for daily events, it serves our community, by giving them the support, space, and frequent events they desire. It advances our theory of change, by empowering locals and bridging their diverse communities. And it puts the MAH at the center of the web of activity, as a valued partner and platform provider.

Building platforms is not the same as building programs. It flexes new muscles, requires different skill sets. But to me, the benefit is clear. In a platform model, our community takes us further than we could ever go on our own.

This was not an event orchestrated by the MAH. It happened because two of our Lost Childhood partners urged it into being. They negotiated with the County. They set the table. They made something real and meaningful happen.

They did it because the exhibition belonged to them. They helped conceive it, plan it, and build it. The Lost Childhoods exhibition is a platform for 100+ partners to share their stories, artwork, ideas, projects, volunteer opportunities, and events.

Nine years ago, I wrote a post called The Future of Authority: Platform Power. In it, I argued that museums could give up control of the visitor experience while still maintaining (a new kind of) power. Museums could make the platforms for those experiences. There is power IN the platform--power to shape the way people participate. This argument became one of the foundations of The Participatory Museum.

Nine years later, I still believe this. Now that I run a museum, I experience the variety of ways we can create platforms that empower community members to do certain things, in certain ways, that amplify the institution. The power IN the platform is real. But I've also become reenergized about the power OF the platform for those community members who participate. I value platforms for their power to scale impact.

Traditionally, museums and cultural organizations offer programs. Staff produce them for, and sometimes with, visitors. Each program has a fixed cost, and expanding that program means expanding that cost. If it takes a staff member 5 hours to run a screen-printing workshop, it takes her ten hours to run it twice. Even a smash hit program is hard to scale up in this model.

At the MAH, we've tried wherever possible to break out of unidirectional program models. We believe that we can most effectively empower and bridge community members (our strategic goal) if we invite them to share their skills with each other. This is the participatory platform model. Instead of staff running workshops, our staff connect with local printmaking collectives. We ask them what their goals are for outreach and community connection. And then we support and empower them to lead workshops and festivals and projects on our site. Instead of "doing the thing" directly, our staff make space for community members to do the thing--and to do so beautifully, proudly, with and for diverse audiences.

Does this work scale better than programs? It's not always obvious from the start whether it will. This work is relationship-heavy, and those relationships take time to build. When we created an exhibition with 100 community members impacted by the foster care system, it took almost a year to recruit, convene, open up, explore, and create the products and the trust to build those products well. But that investment in building a platform paid off.

When you build relationships in a platform, you build participants' power. Platforms can accommodate lots of partners and support them taking the projects in new directions. Since opening in July, exhibition partners haven't just planned a County supervisors' meeting. They've led over 50 exhibition-related community events at and beyond the MAH. They've created powerful learning experiences, diverse audiences, and new program formats. Our staff could never produce all this activity on our own. We put our energy into empowering partners, which ignited their passion and ability to extend the exhibition to new people and places.

Whereas a program is a closed system, a platform is an open one. In a platform model, more is not more staff time and cost. More is more use of the platform, more participants empowered to use it to full potential.

As our organization grows, we are looking for more ways to adopt a platform mindset. Now that we've opened Abbott Square, we have a goal to offer free cultural programming almost every day of the week. This means a huge shift for the MAH (previously we offered 2 monthly festivals plus a few scattered events). How will we increase our event offerings so aggressively? We're not planning to do it by adding a lot of staff to programming the space. We're planning to do it by building new platforms. We are learning from our "monthly festival" platform and building a lightweight, more flexible version. We want to make it easier for community groups to plug in, offering their own workshops and festivals and events, with our support. If we can create the right platform for daily events, it serves our community, by giving them the support, space, and frequent events they desire. It advances our theory of change, by empowering locals and bridging their diverse communities. And it puts the MAH at the center of the web of activity, as a valued partner and platform provider.

Building platforms is not the same as building programs. It flexes new muscles, requires different skill sets. But to me, the benefit is clear. In a platform model, our community takes us further than we could ever go on our own.

Saturday, January 16, 2016

Does Your Institution Have an Advocacy Policy?

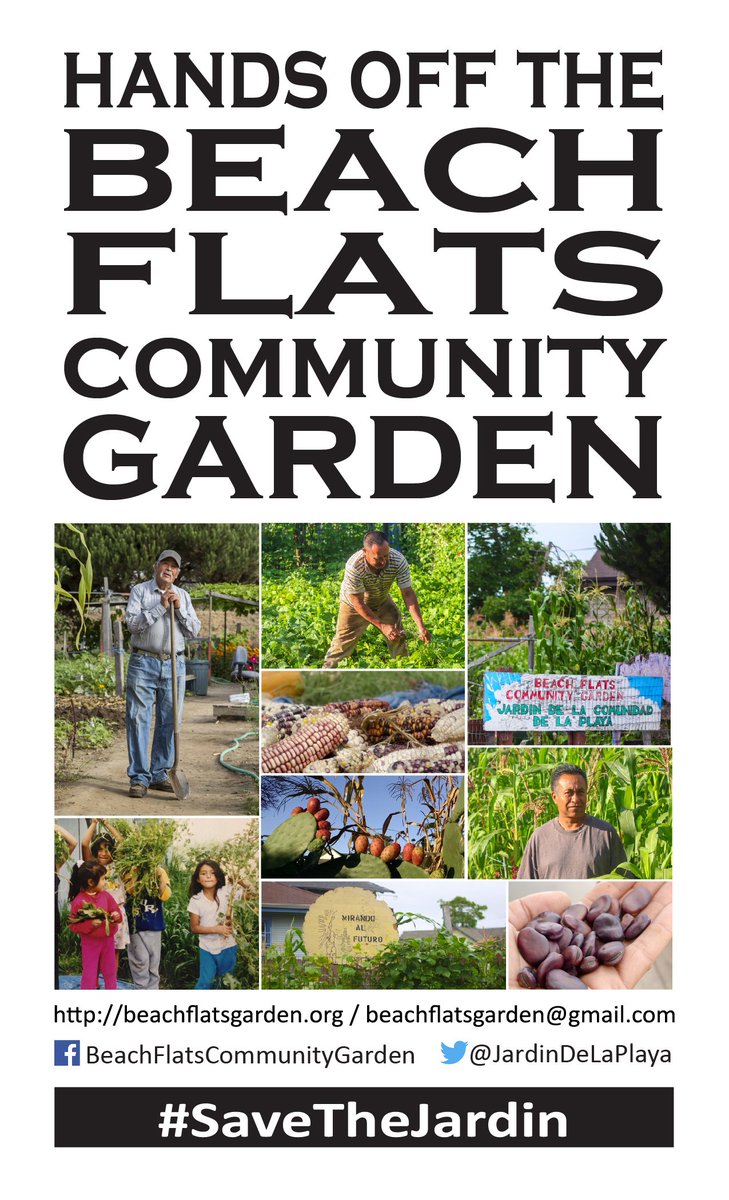

In October of 2015, I got a call from a community partner. The Beach Flats Community Garden was under threat, and this friend of the garden wanted our help. The garden, which had operated for 20 years in a predominately low-income Latino neighborhood near the beach, was losing its lease with a private property owner. The City proposed moving the garden to a nearby plot of City-owned land, but gardeners felt that this disruption would literally uproot an essential community place. Garden supporters and partners were putting together a petition to try to push the City and the property owner to find a long-term solution to allow the garden to remain in place. And so the collaborator on the phone asked: would I sign the petition on behalf of our museum?

The outside partner wasn't the only one asking. Several museum staff members had gotten involved in the political action personally outside of work, and they wanted to know if we could sign on organizationally. This wasn't just a question of what was moral or politically useful in the abstract. It was a question about our commitment to our partners, to local sites of cultural importance, and to the Latino families with whom we have been working intensely to build stronger relationships.

I watched as other partner organizations signed on, uncertain what to do. I didn't know how likely the petition was to have influence, but I knew that signing on was important to the people asking.

Ultimately, I decided we couldn't sign - not because it was the necessarily the wrong thing to do, but because we didn't have any kind of policy beyond directorial discretion to decide when it might be appropriate to take a political stand as an institution.

I took the issue to the board, and we agreed that we need to develop some kind of advocacy policy to be able to answer these phone calls with confidence. Our board/staff advocacy task force is meeting this Friday to get the work started, and so I'm curious: has your organization tackled this question? How have you addressed the challenges and opportunities to raise your institutional voice on local issues?

I'm going into this meeting with a strong feeling that our policy can't be to always say no. Our museum has a growing advocacy component to our work. Our theory of change focuses on an intended impact of building a stronger, more connected community. We already embrace the reality that manifesting that impact requires work beyond our building, beyond traditional museum activities. We are proud of our wide-ranging community partnerships, proud to amplify unsung voices and stories, proud to tackle issues of equity and social justice through our programming.

But that's all work we do on our terms. What good are we as a partner if we can't step up and support our partners on their terms, too? I'd hate to be the kind of organization that embraces partners when we need them but not when they need us.

I don't have an opinion about whether our eventual policy should have enabled us to sign that particular petition. But I do want to see us develop a policy that enables us to address these opportunities thoughtfully, with our mission, theory of change, and community values at heart.

How have you, or would you, go about this? What resources might be helpful as we embark on this work?

If you are reading this via email and would like to share a comment or question, you can join the conversation here.

The outside partner wasn't the only one asking. Several museum staff members had gotten involved in the political action personally outside of work, and they wanted to know if we could sign on organizationally. This wasn't just a question of what was moral or politically useful in the abstract. It was a question about our commitment to our partners, to local sites of cultural importance, and to the Latino families with whom we have been working intensely to build stronger relationships.

I watched as other partner organizations signed on, uncertain what to do. I didn't know how likely the petition was to have influence, but I knew that signing on was important to the people asking.

Ultimately, I decided we couldn't sign - not because it was the necessarily the wrong thing to do, but because we didn't have any kind of policy beyond directorial discretion to decide when it might be appropriate to take a political stand as an institution.

I took the issue to the board, and we agreed that we need to develop some kind of advocacy policy to be able to answer these phone calls with confidence. Our board/staff advocacy task force is meeting this Friday to get the work started, and so I'm curious: has your organization tackled this question? How have you addressed the challenges and opportunities to raise your institutional voice on local issues?

I'm going into this meeting with a strong feeling that our policy can't be to always say no. Our museum has a growing advocacy component to our work. Our theory of change focuses on an intended impact of building a stronger, more connected community. We already embrace the reality that manifesting that impact requires work beyond our building, beyond traditional museum activities. We are proud of our wide-ranging community partnerships, proud to amplify unsung voices and stories, proud to tackle issues of equity and social justice through our programming.

But that's all work we do on our terms. What good are we as a partner if we can't step up and support our partners on their terms, too? I'd hate to be the kind of organization that embraces partners when we need them but not when they need us.

I don't have an opinion about whether our eventual policy should have enabled us to sign that particular petition. But I do want to see us develop a policy that enables us to address these opportunities thoughtfully, with our mission, theory of change, and community values at heart.

How have you, or would you, go about this? What resources might be helpful as we embark on this work?

If you are reading this via email and would like to share a comment or question, you can join the conversation here.

Labels:

advocacy,

relationships,

social justice

Monday, December 28, 2015

Give Yourself Some SPACE in 2016

Every once in a while I look at my growing toddler and think: time will never go backwards. She'll never be this age again. Sometimes, that's a relief. Sometimes, the thought invokes pre-nostalgic fear. But mostly, watching her grow reminds me that time keeps moving relentlessly forward, whether we like it or not.

How do we tackle the problem of time? Some people attack the problem by sleeping less. Some seek to maximize and quantify time, building personal efficiency engines to squeeze out a few more seconds or minutes of joy each day.

In 2016, I'm choosing to take a different approach, inspired by Albert Einstein. I'm confronting the problem of diminishing time by making more space.

When you make space for yourself and others--physically or metaphorically--you expand your world. I've always loved the idea of "space-making" as a strategy for personal care and interpersonal empowerment. This past summer, my museum hosted a retreat for diverse professionals to explore space-making in deep ways. We talked about it. We shared tips and what ifs. We tested out each other's preferred ways of making space, and we tried to develop new space-making solutions to each other's problems.

The result is the Space Deck - 56 ways to make space for yourself and others. 100 extraordinary campers developed hundreds of different spacemaking ideas, which we developed, tested, and distilled into this deck of 56.

Just like a deck of playing cards, The Space Deck is divided into suits, representing different ways to make space through STILLNESS, CREATIVITY, COURAGE, ACTIVISM, RELATIONSHIPS, MOVEMENT, RITUAL, and ENVIRONMENT.

The Space Deck addresses frequent questions at work, like "how can we make space for everyone's voice to be heard in this meeting?," as well as personal questions, like "how can I find some peace in a world of chaos?" The cards share techniques that help you tackle your fears, declutter your mind, connect with your senses, and confront injustice.

You can check out all the spacemaking cards by suit on the Space Deck website. But if you prefer to hold space in your hand (Einstein would approve), you can buy your own personal deck to have and hold. Special thanks to Beck Tench, Elise Granata, Jason Alderman, and all the MuseumCampers who co-created the Space Deck together. All proceeds from Space Deck sales will support future creative retreats and camper scholarships.

Time won't slow down. Instead of trying to race time or trick it or beat it into submission, buy yourself some space in 2016. You'll be amazed how roomy it makes the day.

How do we tackle the problem of time? Some people attack the problem by sleeping less. Some seek to maximize and quantify time, building personal efficiency engines to squeeze out a few more seconds or minutes of joy each day.

In 2016, I'm choosing to take a different approach, inspired by Albert Einstein. I'm confronting the problem of diminishing time by making more space.

When you make space for yourself and others--physically or metaphorically--you expand your world. I've always loved the idea of "space-making" as a strategy for personal care and interpersonal empowerment. This past summer, my museum hosted a retreat for diverse professionals to explore space-making in deep ways. We talked about it. We shared tips and what ifs. We tested out each other's preferred ways of making space, and we tried to develop new space-making solutions to each other's problems.

The result is the Space Deck - 56 ways to make space for yourself and others. 100 extraordinary campers developed hundreds of different spacemaking ideas, which we developed, tested, and distilled into this deck of 56.

Just like a deck of playing cards, The Space Deck is divided into suits, representing different ways to make space through STILLNESS, CREATIVITY, COURAGE, ACTIVISM, RELATIONSHIPS, MOVEMENT, RITUAL, and ENVIRONMENT.

The Space Deck addresses frequent questions at work, like "how can we make space for everyone's voice to be heard in this meeting?," as well as personal questions, like "how can I find some peace in a world of chaos?" The cards share techniques that help you tackle your fears, declutter your mind, connect with your senses, and confront injustice.

You can check out all the spacemaking cards by suit on the Space Deck website. But if you prefer to hold space in your hand (Einstein would approve), you can buy your own personal deck to have and hold. Special thanks to Beck Tench, Elise Granata, Jason Alderman, and all the MuseumCampers who co-created the Space Deck together. All proceeds from Space Deck sales will support future creative retreats and camper scholarships.

Time won't slow down. Instead of trying to race time or trick it or beat it into submission, buy yourself some space in 2016. You'll be amazed how roomy it makes the day.

Monday, November 16, 2015

OdysseyWorks: An Empathy-Based Approach to Making Art

The quest for relevance begins with knowing your audience. Who are the people with whom you want to connect? What are their dreams, their impressions, their turn-offs, their fears?

The quest for relevance begins with knowing your audience. Who are the people with whom you want to connect? What are their dreams, their impressions, their turn-offs, their fears?Ultimately, any approach to answering these questions is limited at some point by the size of the audience involved. When you are dealing with an audience of hundreds or thousands of people, you have to make assumptions. You have to generalize.

But what if you only had an audience of one?

OdysseyWorks is a collective that makes immersive art experiences for one person at a time. They select their audience--by application or commission--and then they spend months getting to know that person. They spend time with them. They call references. They try to understand not just the surface of the individual's personality but the fundamental way that person sees the world. And then, based on their research, they remake the world for a weekend, twisting the person's environment with sensory experiences that explore and challenge their deepest inclinations.

When I first heard about OdysseyWorks, I thought their projects were indulgent novelties. But the more I learned, the more I appreciated their thoughtful slanted window into audience engagement.

OdysseyWorks' projects get to the heart of the fiercest debates in the arts today. Does "starting from the audience" mean pandering to narcissism and dumbing down work? Is it elitist to present art that may be dislocating or foreign? How do we honor the audience's starting point and take them somewhere new?

As artistic director Abe Burickson described their work to me, I imagined Theseus walking deeper into the labyrinth towards the Minotaur. Theseus entered the labyrinth with a string tying him to what he already knew. And then he followed that string into darkness, danger, and ultimately, triumph.

I asked Abe about how he sees the tension between the desire to start with the audience and the desire to move the audience somewhere new. He spoke of the audience as providing a challenge, a challenge like any other artistic constraint. The audience provides an offering of a certain way of looking, a challenge to see the world differently and get inside that perspective with their artwork. OdysseyWorks locates that starting point, hands the audience the string, and draws them further and deeper into mystery.

Abe told me about a performance OdysseyWorks created for a woman named Christina. Christina loved all things symmetrical and tonal. Loved baroque and rococo. Hated Jackson Pollock and John Cage. The OdysseyWorks team is not that way - they like messy and atonal - so it was an interesting challenge. Could they create a space of comfort, a world of her own, and then move her to a space of dischord where the things OdysseyWorks thought were beautiful might become beautiful to her?

Here's how Abe described the project to me:

We started the weekend in Christina's comfort zone. We started with Clair de Lune by Debussy, which she loves, and a few other structured things that worked that way. Over time, she encountered the music in multiple locations--in a symmetrical architectural space, with family.

As the day went on, she relaxed--which is key to the process. When you engage with something, especially something new, you are often on guard, physically, socially, intellectually. You just don’t trust right away.

When you no longer feel that people are judging you, you become much more open to new things. It's really quite amazing how much of a shift can happen.

Once those reservations and judgments faded, we started playing other version of Clair de Lune. There are hundreds of really messed up versions of Clair de Lune. We played them just to shake it up. At one point after seven hours, and about 500 miles of travel, Christina got picked up by a train and was driven to a scene. It was about an hour drive. And in that hour, she just listened to this Clair de Lune version we composed, this 80-minute deconstruction, a slow deterioration, that started classical and ended sounding like people chewing on string. It was beautiful noise. It was the exact opposite of what she liked, and yet by that point, she found it beautiful.

The whole experience was kind of a deconstruction of form. The experience was powerful for her. Later she said it pried her open.

The goal was not that Christina should like John Cage. Nor is it about creating a moment of pleasure. The goal was to create work that is moving for her and a compelling artistic challenge for us. It's about creating a different engagement with life.To me, the biggest aha this story is the middle--the enormous role that the perception of "being judged" plays in narrowing our experience and our openness to new things. When we trust, we open up. But how often does an arts institution start working with an audience by building a trusting relationship (versus bombarding them with content)? What could we gain by starting with empathy instead of presentation?

OdysseyWorks is doing a crowd-funding campaign right now to fund a book project documenting their process. I'm learning from them, so I'm supporting them. Check out their work and consider whether they might help you through the labyrinths in your world.

If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment below. If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

Wednesday, June 03, 2015

Learn to Love Your Local Data

Last month at the AAM conference, a speaker said, "we should all be using measures of quality of life to measure success at our museums."

Imagine a community with 50 different organizations working to reduce childhood obesity. Would you rather see them each pick a measure of success that is idiosyncratic to their program, or join forces to pick a single shared measure of success?

If your museum is working to tackle a broad societal issue, you're not doing it alone. Your program may exist in its own bubble of the museum, but there are likely many organizations tackling the same big issue from different angles.

Each of you is stronger--in front of funders, in front of advocates, in front of clients--if you can work together towards one shared goal. Even if it doesn't map perfectly to your program, it's worth picking a "good enough" measure that everyone can use as opposed to a perfect measure that only works in your bubble.

For example, one of the outcomes in our theory of change that we care about is civic engagement. We want visitors to be inspired by history experiences at the museum to get more involved as changemakers in our community. Our Community Assessment Project already measures indicators of civic engagement like voting, writing to an elected official, and speaking at a public hearing. Are these the indicators we would choose in a bubble? Probably not. But are they more powerful because we have years of good countywide data about them? Absolutely.

Shared data builds shared purpose.

What happens when those 50 different organizations agree on one indicator for success in reducing childhood obesity? They get to know each other. They understand how their individual work fits into a larger picture. They build new partnerships, reduce redundancies in programming, and fill the gaps. They do a better job, individually and collectively, at tackling the big issue at hand.

That's what we should be using measurement to do. I can't wait to hear a story like this at a conference and fall in love with data all over again.

Are you working across your community to share key indicators of success? Share your story, question, or comment below. If you are reading this via email, you can join the conversation here.

I got excited.

"We should identify a few key community health indicators to focus on."

I got tingly.

"And then we should rigorously measure them ourselves."

Ack. She killed the mood.

Many museums (mine included) are fairly new to collecting visitor data. Especially new to collecting data about broad societal outcomes and experiences. Why the heck would we be foolish enough to do it all ourselves?

The "we have to do it ourselves" mantra is one of the most dangerous in the nonprofit world. It promotes perfectionism. Internally-focused thinking. Inability to collaborate and share. Plus, it's expensive. So when we find we can't afford to do it ourselves, we throw up our hands and don't do it at all.

Here are three reasons to find and connect with community-wide sources of data instead of doing it yourself:

The data already exists.

Want to know the demographic spread of your county? Check the census. Want to know how many kids ate fruits and vegetables, or how many teens graduated high school, or how many people are homeless? The data exists. In some communities, it exists in different silos. In others, someone is already aggregating it.

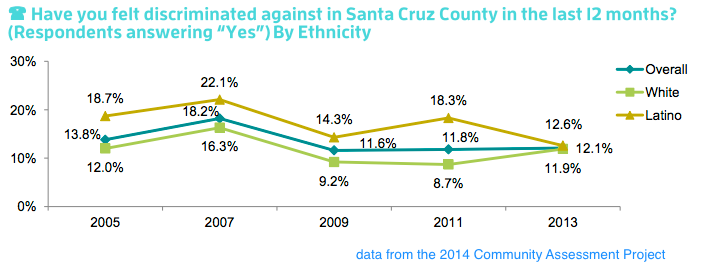

When we started more robust data collection at our museum, we wanted a community baseline. We thought about collecting it ourselves (stupid idea). Instead, we found the Community Assessment Project--an amazing aggregation of data from all over our County, managed by a wide range of stakeholders from health and human services. Not only do they aggregate existing data, they do a bi-annual phone survey to tackle questions like "have you been discriminated against in the last year?" and "what most contributes to your quality of life?" We got the data, and we got involved in the project. Now, instead of using our meager research resources to collect redundant data, we can springboard off of a strong data collection project that we access for free.

You may not have a Community Assessment Project in your community, but you have something. Ask the health department. Ask the United Way. Someone is collecting baseline community data. It doesn't have to be you.

We're stronger together.

Imagine a community with 50 different organizations working to reduce childhood obesity. Would you rather see them each pick a measure of success that is idiosyncratic to their program, or join forces to pick a single shared measure of success?

If your museum is working to tackle a broad societal issue, you're not doing it alone. Your program may exist in its own bubble of the museum, but there are likely many organizations tackling the same big issue from different angles.

Each of you is stronger--in front of funders, in front of advocates, in front of clients--if you can work together towards one shared goal. Even if it doesn't map perfectly to your program, it's worth picking a "good enough" measure that everyone can use as opposed to a perfect measure that only works in your bubble.

For example, one of the outcomes in our theory of change that we care about is civic engagement. We want visitors to be inspired by history experiences at the museum to get more involved as changemakers in our community. Our Community Assessment Project already measures indicators of civic engagement like voting, writing to an elected official, and speaking at a public hearing. Are these the indicators we would choose in a bubble? Probably not. But are they more powerful because we have years of good countywide data about them? Absolutely.

Shared data builds shared purpose.

What happens when those 50 different organizations agree on one indicator for success in reducing childhood obesity? They get to know each other. They understand how their individual work fits into a larger picture. They build new partnerships, reduce redundancies in programming, and fill the gaps. They do a better job, individually and collectively, at tackling the big issue at hand.

That's what we should be using measurement to do. I can't wait to hear a story like this at a conference and fall in love with data all over again.

Are you working across your community to share key indicators of success? Share your story, question, or comment below. If you are reading this via email, you can join the conversation here.

Labels:

informatics,

relationships,

research

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

How Do You Define "Community?"

Close your eyes and imagine your organization's "community." Is it a mist of good feeling? A fellowship of uncertainty? Does it have a human face?

Communities are made of people, not rhetoric. You can define a community by the shared attributes of the people in it, and/or by the strength of the connections among them. When an organization is identifying communities of interest, the shared attribute is the most useful definition of a community. The second is a quality of the community (strong vs. weak) as defined.

I've been exploring three different lens for defining community: geography, identity, and affinity.

A community by GEOGRAPHY is defined by place. It is made up of the people attached to a given location: a city, a district, a neighborhood, a country. The simplest version of this community is the place where you live. But you might also feel part of a geographic community related to the place you grew up, or a place you used to live, or a place you often visit.

A community by IDENTITY is defined by attributes. It is made up of people who end the sentence "I am _____" in the same way. Jewish. Chicano. Fifth generation. Artist. Some identities are self-ascribed (like "vegetarian") whereas others are assigned externally (like "black").

A community by AFFINITY is defined by what we like. It is made up of people who end the sentence "I like _____" or "I do ______" in the same way. Knitters. Surfers. Punks. People who go to midnight movies. Some affinities are lifelong passions. Others are passing fancies.

These types aren't perfectly distinct. A community of people who go to trivia night at a given bar could identify by geography (the bar), identity (nerds), or affinity (trivia).

How much does the strength of connections among members matter to the definition of community? It matters in degree but not in kind. A strong community engenders fellowship among members, advances specific social norms, and has identifiable leaders. Weak communities are more diffuse, with members who may not even be aware of each other. These differences are useful when considering how and who to reach out to when trying to get involved with a new community. But the community exists whether it is strong or weak.

Maybe you want to work with Hmong immigrants to Minnesota. Or art-lovers of Brooklyn. Or Santa Cruz County teens who want to make social change. Communities may be huge and diffuse, or niche and tightly connected. The key is to be specific in who you seek. My biggest fear about "community engagement" is that it is too vague. It's easy to say "yep, we do that" if you aren't clearly defining the work and the people involved. Defining the community turns an amoebic concept into a human reality.

How do you define "community" in your work?

If you are reading this via email and would like to share a comment or question, you can join the conversation here.

p.s. I'll be speaking on these topics at the AAM conference next week. Scroll down in this post to learn more.

Communities are made of people, not rhetoric. You can define a community by the shared attributes of the people in it, and/or by the strength of the connections among them. When an organization is identifying communities of interest, the shared attribute is the most useful definition of a community. The second is a quality of the community (strong vs. weak) as defined.

I've been exploring three different lens for defining community: geography, identity, and affinity.

A community by GEOGRAPHY is defined by place. It is made up of the people attached to a given location: a city, a district, a neighborhood, a country. The simplest version of this community is the place where you live. But you might also feel part of a geographic community related to the place you grew up, or a place you used to live, or a place you often visit.

A community by IDENTITY is defined by attributes. It is made up of people who end the sentence "I am _____" in the same way. Jewish. Chicano. Fifth generation. Artist. Some identities are self-ascribed (like "vegetarian") whereas others are assigned externally (like "black").

A community by AFFINITY is defined by what we like. It is made up of people who end the sentence "I like _____" or "I do ______" in the same way. Knitters. Surfers. Punks. People who go to midnight movies. Some affinities are lifelong passions. Others are passing fancies.

These types aren't perfectly distinct. A community of people who go to trivia night at a given bar could identify by geography (the bar), identity (nerds), or affinity (trivia).

How much does the strength of connections among members matter to the definition of community? It matters in degree but not in kind. A strong community engenders fellowship among members, advances specific social norms, and has identifiable leaders. Weak communities are more diffuse, with members who may not even be aware of each other. These differences are useful when considering how and who to reach out to when trying to get involved with a new community. But the community exists whether it is strong or weak.

Maybe you want to work with Hmong immigrants to Minnesota. Or art-lovers of Brooklyn. Or Santa Cruz County teens who want to make social change. Communities may be huge and diffuse, or niche and tightly connected. The key is to be specific in who you seek. My biggest fear about "community engagement" is that it is too vague. It's easy to say "yep, we do that" if you aren't clearly defining the work and the people involved. Defining the community turns an amoebic concept into a human reality.

How do you define "community" in your work?

If you are reading this via email and would like to share a comment or question, you can join the conversation here.

p.s. I'll be speaking on these topics at the AAM conference next week. Scroll down in this post to learn more.

Labels:

inclusion,

relationships

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Making Meaningful Connections: Inspiring New Report from Irvine and Helicon

Our work to transform the Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History into a participatory and community-centered place has been heavily supported by the James Irvine Foundation. I've learned a lot from Irvine Foundation staff and partners directly. But one of my favorite things they do is remarkably unpersonalized: they produce killer reports.

Their newest one, Making Meaningful Connections, was written by Holly Sidford, Alexis Frasz, and Marcy Hinand at Helicon. The report is a slim 12 pages on the common characteristics of arts organizations that successfully and continuously engage diverse audiences. It is paired with a thoughtful infographic (part of which is shown at the top here) that summarizes their findings.

Making Meaningful Connections is not riddled with jargon and academic theory. Nor is it packed with juicy examples and case studies. Instead, it's a tight, inspiring, and reasonably original brief on the strategies that lead to sustained involvement of diverse people with arts organizations. It's the first report in a long time that I am sharing with my board. (The last one was on arts innovation and change, also from Irvine.)

Here are three aspects of Making Meaningful Connections that I like most:

What did you get out of Making Meaningful Connections?

Their newest one, Making Meaningful Connections, was written by Holly Sidford, Alexis Frasz, and Marcy Hinand at Helicon. The report is a slim 12 pages on the common characteristics of arts organizations that successfully and continuously engage diverse audiences. It is paired with a thoughtful infographic (part of which is shown at the top here) that summarizes their findings.

Making Meaningful Connections is not riddled with jargon and academic theory. Nor is it packed with juicy examples and case studies. Instead, it's a tight, inspiring, and reasonably original brief on the strategies that lead to sustained involvement of diverse people with arts organizations. It's the first report in a long time that I am sharing with my board. (The last one was on arts innovation and change, also from Irvine.)

Here are three aspects of Making Meaningful Connections that I like most:

- New participant relationships are like new friendships. They take time, curiosity, respect and the willingness to be changed by the relationship. The report starts with an elegant friendship analogy (see the box on page 4) that breaks down the challenges of genuine arts engagement in a clear, relatable, and motivating way.

- Targeted programming is not enough. The authors name the reality that one-off programs, exhibits, or shows for specific groups do little to change the mix of participants longterm. Interestingly, they argue instead that structural change--including but not exclusively programmatic change--is what makes the difference in participant makeup. They also acknowledge that some organizations are happy with their participant makeup, and that these multi-faceted organizational shifts are voluntary for those who want them.

- The characteristics of successful organizations involve deepening, not adding. So often, these kinds of reports recommend a long list of changes and new things to add to your work. It can feel defeating or downright impossible to integrate them into already-strapped schedules. But this report was developed based on existing organizations and practices, looking for common characteristics as opposed to new directions. The recommendations read less like "thou shalt do this new thing" and more like "deepen and embed in this thing you already have." We all have missions. We all have leaders. We all have business models. We can all shift within our existing worlds.

And here are two things I wonder about:

- Universalist tone. This report could come from--and go--anywhere. I assume that's intentional, and for the most part, it's a good thing. The report is brief, clear, and open. If you are reading this report in Manchester or Malaysia or Memphis, you will find meaningful and useful content. On the other hand, the Irvine Foundation makes grants specifically in California. When Josephine Ramirez, Program Director for the Arts, introduced the report on the Irvine blog, she did so in the context of a state that is now 55% Latino and Asian. Nowhere in the report itself is there a comparable framing statement about why it is urgent to consider this work now, in California and around the world. Perhaps it's self-evident. But especially for organizations where cultural competency is in its infancy, those starting points and case statements are still necessary. Then again, Irvine made that statement pretty clearly in a previous report.

- Recommendation to bring practices "into balance." I didn't find it meaningful to imagine an institutional "balance" of the five recommended practices (welcoming spaces, relevant programming, respectful relationships, analysis for improvement, business model). I agree that all are important, and that they are interrelated, but I didn't see a rationale in going for parity. I'd like to understand more about the basis for that recommendation.

What did you get out of Making Meaningful Connections?

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Who is an Artist? On Naming and Expertise

Rebecca sat down next to me at breakfast and asked, "How was the hike yesterday?"

I replied, "Good. It was more of a walk. But it was beautiful."

Her: "You're a serious hiker, right?"

Me: "I guess so."

This simple exchange--or one like it--happens every day. We question our abilities. We confirm our expertise.

I noticed this conversation because it happened during a break at a two-day meeting where people heatedly debated the question of who is an artist. In that context, this simple exchange about hiking got me thinking.

What does it mean when someone says she is a hiker, or a scientist, or an artist? It can mean:

I replied, "Good. It was more of a walk. But it was beautiful."

Her: "You're a serious hiker, right?"

Me: "I guess so."

This simple exchange--or one like it--happens every day. We question our abilities. We confirm our expertise.

I noticed this conversation because it happened during a break at a two-day meeting where people heatedly debated the question of who is an artist. In that context, this simple exchange about hiking got me thinking.

What does it mean when someone says she is a hiker, or a scientist, or an artist? It can mean:

- I do this thing often.

- I do this thing at a high level of ability.

- I have expertise in doing this thing.

- I make my living doing this thing.

- I consider this thing to be a core part of my identity.

- I affiliate with this thing.

- I aspire to do this thing professionally, and I am affiliating to build that future for myself.

Some professionals believe strongly in the power of aspirational affiliation. Last week, I heard a curator advocate strongly for the "everyone is an artist" frame of thinking. When you tell a child or an outsider that he is an artist, you empower that person to join a community of art-making. At the same time, you expand the definition of art and make it more inclusive.

Other professionals believe that expertise needs to be protected. Last week, I heard an immensely talented performer say he "dances but isn't a dancer" because he doesn't do it every day. A person who dedicates their life to making art has a different way of seeing and engaging with the world. It's valuable to honor and acknowledge that difference.

Each of us defines these lines differently, and I don't think there can be one answer. There are reasonable arguments for delineation based on credentials, experience, talent, intention, time on task, and personal connection.

I know within myself, in the small example of hiking, I froze for a moment when I was asked if I was a serious hiker. I started thinking: well, yes, this is a big part of my identity, but I don't really do it that often anymore, but I like to do it at a high level of intensity, and compared to the general public I do it a lot, and I often plan vacations around it, and probably when I am in a less crazy time of life I'll do it more...

I experienced a half-second of heart-racing existential self-questioning just to answer a very simple question.

I also noticed a kind of social distinction shaping up around the exchange. When I said "it was more of a walk," I was also saying "this isn't up to my standards of hiking." When she asked, "You're a serious hiker, right?," she was also asking, "You distinguish yourself from others in this way, right?" The use of the word "serious," like the use of the word "professional," started to draw a clearer line between me and Rebecca--a line that made me uncomfortable. I didn't want to exclude her from past or potential shared hiking experiences. But subtly, I did.

All of this makes me think three basic things about how we name ourselves:

- It's personal. Even if you think you have the way to define who is an artist or a scientist or an expert, each individual may still choose to affiliate (or opt out) based on his/her own standards.

- It's relational. The things we call ourselves and each other do impact the way we see and treat each other.

- It could be much richer and more expansive. A word like "artist" is a heavy hammer to impose on every nail. If the Eskimos have fifty words for snow, can't we have fifty words for artist? If we can add more nuance to the ways we name ourselves, we can move from debate to dialogue about the opportunities inherent in a diverse and complex world.

How do you interpret the question of who is an artist/scientist/expert?

Labels:

inclusion,

relationships

Wednesday, May 22, 2013

Thinking about User Participation in Terms of Negotiated Agency

Early this month, I got the chance to hear legendary game designer Will Wright (Sim City) give a talk. I've followed Wright's work for years because of his unique perspective on the potential for game-players to be game-makers - in other words, to co-create the gaming experience.

In his talk, Wright said one thing that really stood out:

"Negotiated agency" strikes me as a really useful framework in which to talk about visitor/audience participation in the arts. "Negotiation" implies a respectful relationship between institution (or artist) and user. The institution initiates the negotiation with a set of opportunities and constraints. But users play a role via their own agency--both in how they engage and when they break the rules.

Sometimes the negotiation works beautifully. You offer visitors markers and tape and a wall, and they agree tacitly only to write on the tape and not on the wall itself.

Sometimes the negotiation is contested. You tell people they can't take photographs in the gallery or the performance, but the phones sneak out, covertly or defiantly, to reassert personal control of the experience. Patrons clap between movements. Visitors talk over the tour guide.

Sometimes the negotiation can be exploited for artistic means. The theater is dark and the artist breaks the fourth wall and asks for conversation. The symphony conductor asks everyone to raise their phones and join the orchestra. The museum invites art-making in the elevator. This is a kind of negotiation jui-jitsu that can create art through creative tension.

In my experience, this negotiation works best if we acknowledge people's agency and seek ways to create something surprising and high-value through it.

And so I humbly submit two questions to ask yourself when thinking about user participation:

In his talk, Wright said one thing that really stood out:

Game players have a negotiated agency that is determined by how the game is designed.In other words, the more constrained the game environment, the less agency the player has. The more open, the more agency. Think about the difference between Pacman and Grand Theft Auto. Both games have a "gamespace" in which they are played. Both games have rules. But Grand Theft Auto invites the player to determine their own way of using the space and engaging with the rules. The player's agency is not total, but it is significant.

"Negotiated agency" strikes me as a really useful framework in which to talk about visitor/audience participation in the arts. "Negotiation" implies a respectful relationship between institution (or artist) and user. The institution initiates the negotiation with a set of opportunities and constraints. But users play a role via their own agency--both in how they engage and when they break the rules.

Sometimes the negotiation works beautifully. You offer visitors markers and tape and a wall, and they agree tacitly only to write on the tape and not on the wall itself.

Sometimes the negotiation is contested. You tell people they can't take photographs in the gallery or the performance, but the phones sneak out, covertly or defiantly, to reassert personal control of the experience. Patrons clap between movements. Visitors talk over the tour guide.

Sometimes the negotiation can be exploited for artistic means. The theater is dark and the artist breaks the fourth wall and asks for conversation. The symphony conductor asks everyone to raise their phones and join the orchestra. The museum invites art-making in the elevator. This is a kind of negotiation jui-jitsu that can create art through creative tension.

In my experience, this negotiation works best if we acknowledge people's agency and seek ways to create something surprising and high-value through it.

And so I humbly submit two questions to ask yourself when thinking about user participation:

- What is our negotiating stance in developing this relationship with participants? How can we make it a win-win?

- How will participants seek to assert their agency in the experience? Will we encourage these activities, denounce them, or divert them?

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Guest Post: Radical Collaboration - Tools for Partnering with Community Members

This guest post was written by my incredible colleagues, Stacey Marie Garcia and Emily Hope Dobkin, with minimal input from me. It started as a handout for a session that Stacey and I are doing at the California Association of Museums, and then I realized it was so darn useful that it was worth sharing with all of you. Can't wait to hear what you think.

The majority of our public programs at the Santa Cruz Museumof Art & History are created and produced through community collaborations. Each month we work with 50-100 individuals to co-produce our community programs. It’s not unusual for us to meet with an environmental activist, a balloon artist, a farmer, and the Mayor of Santa Cruz all in one day. Every time we collaborate, we learn new ways to improve our process, organization and communication.

We never received a “how-to-guide” for collaborating with community members here at the MAH, but over time, we have acquired some basic tools that have shaped our approach. We realize collaboration differs greatly for each individual and organization. We offer these tools in the spirit of sharing and look forward to learning about the techniques you use in your own community.

Here are some other ways we compensate our collaborators:

The majority of our public programs at the Santa Cruz Museumof Art & History are created and produced through community collaborations. Each month we work with 50-100 individuals to co-produce our community programs. It’s not unusual for us to meet with an environmental activist, a balloon artist, a farmer, and the Mayor of Santa Cruz all in one day. Every time we collaborate, we learn new ways to improve our process, organization and communication.

We never received a “how-to-guide” for collaborating with community members here at the MAH, but over time, we have acquired some basic tools that have shaped our approach. We realize collaboration differs greatly for each individual and organization. We offer these tools in the spirit of sharing and look forward to learning about the techniques you use in your own community.

Start with and continuously identify your communities.

- Who are they?

- What are their needs?

- What are their assets?

- Who is represented in your museum? Who isn’t?

Reach out to and continuously seek diverse collaborators--not just the usual suspects.

We look for partners who have:

- An understanding of and desire to help meet your community’s needs.

- Incredible assets, skills and resources to offer to your community but they are in need of more awareness, promotion, visibility and representation.

- A genuine enthusiasm for sharing their skills, building knowledge and developing relationships in the community even if they haven’t done it before. For example, a few months ago we had a couple approach us to propose a Pop-Up Tea Ceremony. Their enthusiasm and commitment charmed us and aligned with our social bridging goals. We invited them to set up the day after we met them and they’ve been Friday regulars ever since.

- Experience working with a wide variety of age groups or teaching in general.

- Good communication skills and are kind and friendly.

- Large and small (or no) followings. When planning programs or events, we involve a combination of these groups to share and bridge audiences, bringing big, diverse crowds to new artists and ideas.

Openly invite collaboration by establishing and maintaining transparency about your partnerships with the public and fellow staff members.

- On your website: share your programing goals, solicit collaborations in general and for specific events, provide easily accessible staff contact information, clearly state how your collaborations function, give thanks and acknowledgement to your collaborators through your website and on Facebook page.

- At your museum: have your front desk staff aware of upcoming events and collaboration possibilities, always have business cards available for visitors interested in collaborating so they can easily contact staff members. Be available to talk with people at your events and hand out your contact information to anyone who has an idea they’d like to talk with you about or is interested in helping. Follow up with them later.

- Don’t pass judgment or make assumptions. Always be open to discussing collaborative possibilities with anyone and everyone and then decide if it’s a good fit.

- Mine your colleagues; ask for ideas and suggestions from staff members for resources. You never know who might have connections to some place or another. For our Art That Moves event, our Membership and Development Director suggested the incredibly popular Tarp Surfing activity.

Always meet your collaborators in person. We can’t overstate how important this is to getting everyone moving in the same direction.

- Clearly explain how your organization collaborates with others before you meet.

- Meet them at your museum so they begin to become more familiar and comfortable with the space and understand how they will fit into the event or program.

- Ask them about their goals for this collaboration and share your goals.

- Find a way, together, to achieve both.

- Brainstorm together your wildest ideas and then scale back. For our 3rd Friday series, we like to have an initial meeting with all of our collaborators and together go over the community program goals tied to the theme of the event. Incredible projects can arise when you have a poet, a librarian, a printmaker, a bookbinder and a teacher all throwing out ideas together. (Radical Craft Night and Poetry & Book Arts)

- Allow time to pass for further individual reflection, for them to share their ideas with other members of their organization and for you to give it further thought.

- Confirm final details with them over phone, email or go to their location this time.

Collaboration is based upon communication. Get ready to talk.

- Be prepared to spend an enormous amount of time communicating with each individual through email, over the phone and in person.

- Make time for them. When you give collaborators more of your time, they will feel more confident about their role in the event, their project/workshop/demonstration will inevitably be stronger and your visitors will be happier.