When I was

little, my uncle drove me to see a real big top circus. I don’t quite remember

where it was, somewhere over in the farmlands near Santa Cruz, like Gilroy or

Watsonville. Like so much of those valleys, I mostly remember the lush

flatness, in this case with the red tent popping up like a mirage. I was

younger than school age, and little from that circus visit remains in my

memory.

One

distinct memory I have, to this day, was of a single one-man, or we might say one -person band. He wandered

around the big top playing music with his jiggered musical contraption attached

to his body. As a kid, this one-person band didn’t seem all that extraordinary.

The guy after him was on a unicycle juggling rubber chickens, after all.

Seemingly without thought, cymbal hand and kazoo mouth sounded in time with

keyboard hand and horn foot. Everything ordered, everything in time, everything

easy.

But, now

as an adult, I am amazed at the guy’s ability to move his limbs in harmonious

synchronicity. I can barely drink coffee and read my email some mornings, let

alone play a full symphony alone. (Of course, I was four when I saw the guy. It

might have been barely a harmony.)

I tell the

story of the one-person band because I think many museum professionals feel like

him. We are spinning and performing, and most people have no idea of the

preplanning it takes to make it look so easy. But, most importantly, few museum

professionals have a free hand or moment. We are just doing our best to keep

from going off-key.

Last week,

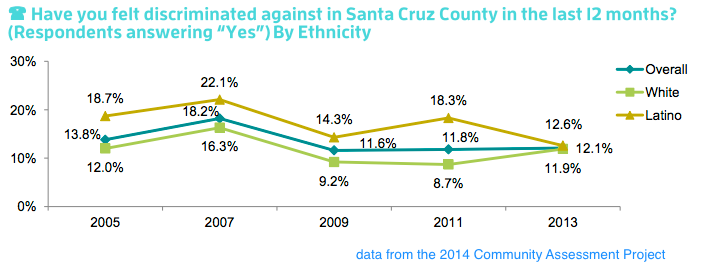

I asked what are the barriers to keep us from throwing open the doors. There

are plenty. We might think of structural racism or the classism inherent in our

funding structures. I hope to hear you articulate your thoughts in comments or

on social.

Today, I’d

like to call out a huge one. We will always find it hard to implement equity

and access, metaphorically throwing open the doors, if our leaders don’t spend

time thinking about how we do our work. We can’t serve our patrons if we

are not thinking about the people doing the work.

Museums

rarely have the funding to replicate positions. If the building operations guy

is sitting with you in a meeting, there is no second building operations person

at his desk. If you have a teen program running, there are no second teen

programs person out drumming up business. While we might not play accordions

with our feet while shaking maracas, most museum professionals are orchestrating

huge amounts of disparate forms of labor all the while making it look

effortless.

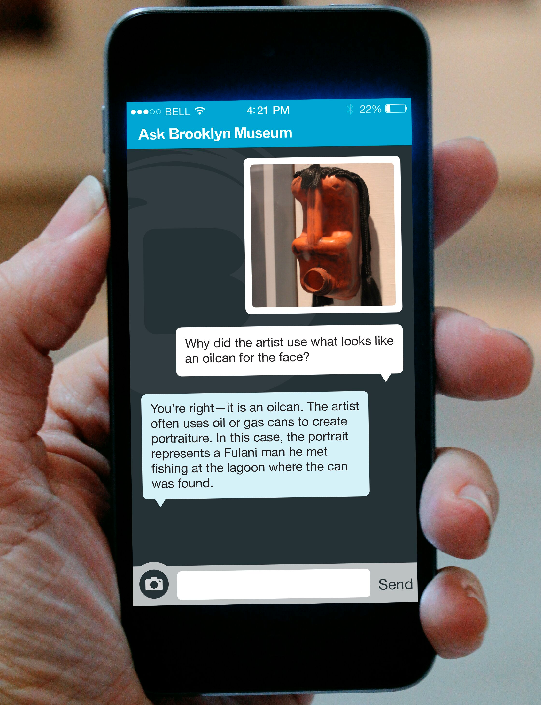

As a

field, we spend a whole lot of time evaluating patron’s experiences (hopefully).

Museums are for people, after all. But patrons are only a portion of the people

in museums. Staff is an important part of the equation. The systems that staff

work with can be empowering or inveigling. So much of our work is collective, a

lifelong group project. But as a field, we don’t always articulate our work

norms to each other. Our organizations often have people playing different

songs, with earplugs on, instead of finding ways to perform together.

What’s the

solution? Well, noticing each other, listening carefully, and trying solutions.

We do this for our visitors (hopefully). Why not for staffing functions?

Recently,

my amazing colleagues and I have started to articulate and improve many aspects

of our work. For example, we are working out what needs a meeting and what can

use an email, writing out process documents, and then putting these efforts

into action. This is stuff that any workplace does, ad hoc, but we are trying

to be purposeful and thoughtful. Why? Because while we want to do the real

work, we first have to work out how to best keep our own sanity. If we can as a

staff decrease the cognitive load of our everyday work, think of how far we can

fly. I am humbled by how awesome my colleagues have been to take the leap with

me. We’re not quite at the point where we can share all our efforts, though we

will eventually. But, in a broad sense, we are trying to be purposeful in how

we do our work, so we can free ourselves up to do our work better. BTW, Thank

you. Thank you, awesome colleagues.

To take it

back to this month’s topic, what is holding back our ability to metaphorically throw

open the doors? Time and energy are finite resources. Are we using them well? Work

practices can be a boon, helping you do more better. But efficient and

effective work practices take thought and refinement. Most museum workplaces

don’t place energy or thought into work practices as they focus their scant

energy on collections or visitors. If you can spend real time on improving

work, you might find yourself freed up, emotionally and with labor. With that

freedom, you might feel giddy and free—so free you decide it’s time to plan to

throw open the doors.

Managers have a huge part in this. Leaders often look at

their best staff, and think, ‘hey let’s put them on this project.’ But what

they might not realize is that they are potentially destabilizing that

employee. They are asking the one-person band to jump on a unicycle. Now, maybe

that performer can do that, but he will need time to practice and fall.

Similarly, when good employees are asked to take on more thing, they will need

time to fail. Many of our institutional efforts at throwing open the doors, add

labor to staff. But, leaders don’t create the systems to understand how it

impacts overall work. We are asking our staff to perform without a net with

their hands tied behind their back. They can’t throw open the doors.

What’s the solution? Leaders need to realize access and equity

isn’t solely about visitors. It’s about systems and staff too. They need to

think holistically and carefully. They need to put in the effort to support

their staff and try to support process improvements. They also need to honor

the careful orchestration that happens in every museum in the country, with

each museum professional, spinning, dancing, and performing amazing feats every

day.

---

Also, please consider passing on your ideas about what keeps

us from throwing open the doors. Tag me so I can add your thoughts to this

month’s summary post @artlust on twitter, @_art_lust_ on IG, & @brilliantideastudiollc on FB).

Thanks to Cynthia Robinson of Tufts University for talking out the one-man/ one-person band. I appreciate her reaching out and discussing it. I was worried one-person band wouldn't work since one-man band is common idiom. But we agreed one-person works--we are flexible, equitable thinkers after all. I write these things late in the evenings alone. Without a sounding board in person, I need your voices to help me.

Thanks to Cynthia Robinson of Tufts University for talking out the one-man/ one-person band. I appreciate her reaching out and discussing it. I was worried one-person band wouldn't work since one-man band is common idiom. But we agreed one-person works--we are flexible, equitable thinkers after all. I write these things late in the evenings alone. Without a sounding board in person, I need your voices to help me.