This week has turned out to be the hardest post I've written yet. Not because of the subject matter, but because of the sheer volume of awesome I'm trying to summarize. This month, we're thinking about the way we do work in museums. I'd ask questions on Twitter before. But this one resonated clearly, as I got 75 retweets and 61 comments. So many wonderful ideas, and I shared a few below.

An important thread throughout was that managers can use their power for good. A few offered solid concrete suggestions that take the big idea of "advocacy" and make it concrete, like list wages on hiring requests and refusing to use unpaid interns. Also, being flexible about work times, as both Jennifer Foley and Emily Lytle-Painter amongst others mentioned. Work isn't prison; don't make them feel like they're doing time.

But, being a manager is a learned skill. A few suggestions were about outside training to improve your skills. Everyone can learn from others. Training, reading, and practicing are three key elements in becoming a better leader. As someone texted me recently, Art History grad school didn't teach us anything about working with others in museums. We all need help to do this better. And there are many sources out there. I've been reading non-stop in the last few months, let me tell you. And here are a few suggestions from commenters. Dan Hicks suggested:

Nikhil Trivedi suggested reading Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun's White Supremacy Culture document and reflecting on how those issues relate to management. Many others suggested articles to read. Sharing articles that work is a great reason to stay on Museum Twitter by the way.Build #PositiveAction training—as defined in the 2010 Equality Act—to make a 'pipeline' to begin to address under-representation. In a small way we've begun such a process with the new collaborative PhD funding in Oxford's Museums, Libraries and Gardens https://t.co/DfaMvVJvbK— Dan Hicks (@profdanhicks) November 11, 2019

Managing also requires understanding the work that happens in your departments and the workers who do that labor. Dan Brennan had a plan that is powerful and simple. Everyone can do it today:

Some suggestions were about gaining empathy and looking for solutions by seeing work differently, like Micah Walter who suggested:Periodically write down your understanding of what everyone on your team does, then submit it to them for revisions.— Dan Brennan (@danieltbrennan) November 11, 2019

Others, like Suse Anderson, also talked about swapping as a way to help you see the big picture from another point of view. Much of leadership is advocacy for your team, and it's hard to do that without understanding their work.Swap desks with one of your team. Sit there for a week and then rotate to someone else.— Micah 🍂 Walter (@micahwalter) November 11, 2019

Many people suggested regular one on one meetings with colleagues. (I get they are on your team if you are a leader, but they are not your staff. They are staff of your organization, and you lead them.)

Learning alongside your team was a suggestion that went across many comments. One such way to learn with your colleagues is:1x1 time is critical. Meet with every direct report at least once a week (I ♥️ walking meetings to open up our lungs and our thinking). Ask your staff what support they need--from you and from elsewhere--and do everything you can to get it for them. Read Fierce Conversations.— Dana Allen-Greil (@danamuses) November 13, 2019

Making work visible is a favorite topic of mine. Understanding why people do what they do, and how much they have to do, helps organizations run better. Lindsay Green suggests:Set aside regular time for their unit to engage in their own professional development. Book group, conversation, whatever. Make it predictable, make it regular. Create the expectation that everybody needs to keep learning.— Ed Rodley (@erodley) November 12, 2019

Many people discussed good leaders as being people who help staff look forward, not just for the organization, but for their team member's own growth. Part of a leader is telling your staff you advocate for their future. Ask your teams where they want to be in a few years, and work with them to get there. Jenn Edgington said:I’ll go with make the work the team are focussed on visible - literally a list of projects or challenges you’re currently solving on the wall. Over delivery/lack of focus/too many small side projects is burning through people and their enthusiasm for the work.— Lindsey Green (@lindsey_green) November 12, 2019

Letting your staff look forward also requires allowing them to shine for the work they do today. Credit is infinite; let them enjoy the benefits of their labor. Find ways they can get their own voices out there, either by encouraging them to go to conferences (and financially supporting that) or helping them find publishing opportunities.Help build skills in their employees not only to do their current job but also to prepare for next steps.— Jenn Edginton (@edgerington) November 11, 2019

Also practice empathy, and gratitude. Support team members and be an advocate for them.

Though with both, try to find ways to make sure this doesn't add labor. If they are writing an article you want them to do, you have to find space in their workload. Or rather, you have to ask them to find space in their workload. Allow them to decide, using their knowledge of their work, where space could open to open up to do that presentation or paper.Share, encourage and give your team (and your interns) the opportunity to attend talks, symposiums, and conferences. The topic of the event also need not be directly related to the work they do. Exposure to all sectors of museum work is important.— Michelle Kuek (@greenteafields) November 12, 2019

Circling back to the idea of the power of the manager, you have the power to say yes or no to all sorts of things. Museums are "no" cultures, often for good reason. Dance while juggling flaming sticks in front of tapestries? No. Tell untruths about collections? No. But that no culture also often translates into a no culture in the workplace. Changing that can be powerful, as Nathan Lachenmyer says:

Managers need to model working smart. As Katie Eagleton reminds me--I mean all of us:Say yes to someone on your team that has a crazy sounding idea.— nathan lachenmyer (@morphogencc) November 11, 2019

Build around motivated individuals on your team, give them the support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

Overall, the biggest topic that came up was to communicate. As Kate Livingston suggests:Encourage people in your team not to work evenings/weekends/whenever their scheduled time off is - people need rest, and a life outside work even (perhaps especially) if they do a job they are passionate about. And set the right example by not doing it yourself, either.— Katie Eagleton (@fearandsequins) November 12, 2019

Now, I've only hit the top level of comments, I'd invite you to move over to Twitter to read the full thread:1st: Ask themselves and their teams/colleagues the exact question you posed— “What is one concrete thing I could do today to make the field better?” 2nd: Listen openly, deeply, and with intention to each answer. 3rd: Take at least one action based on what is heard. Today.— Kate Livingston (also see @CoachKateLiv) (@exposyourmuseum) November 11, 2019

Blog research: What is one concrete thing any museum manager could do today to make the field better? RT Please.— Seema Rao (@artlust) November 11, 2019

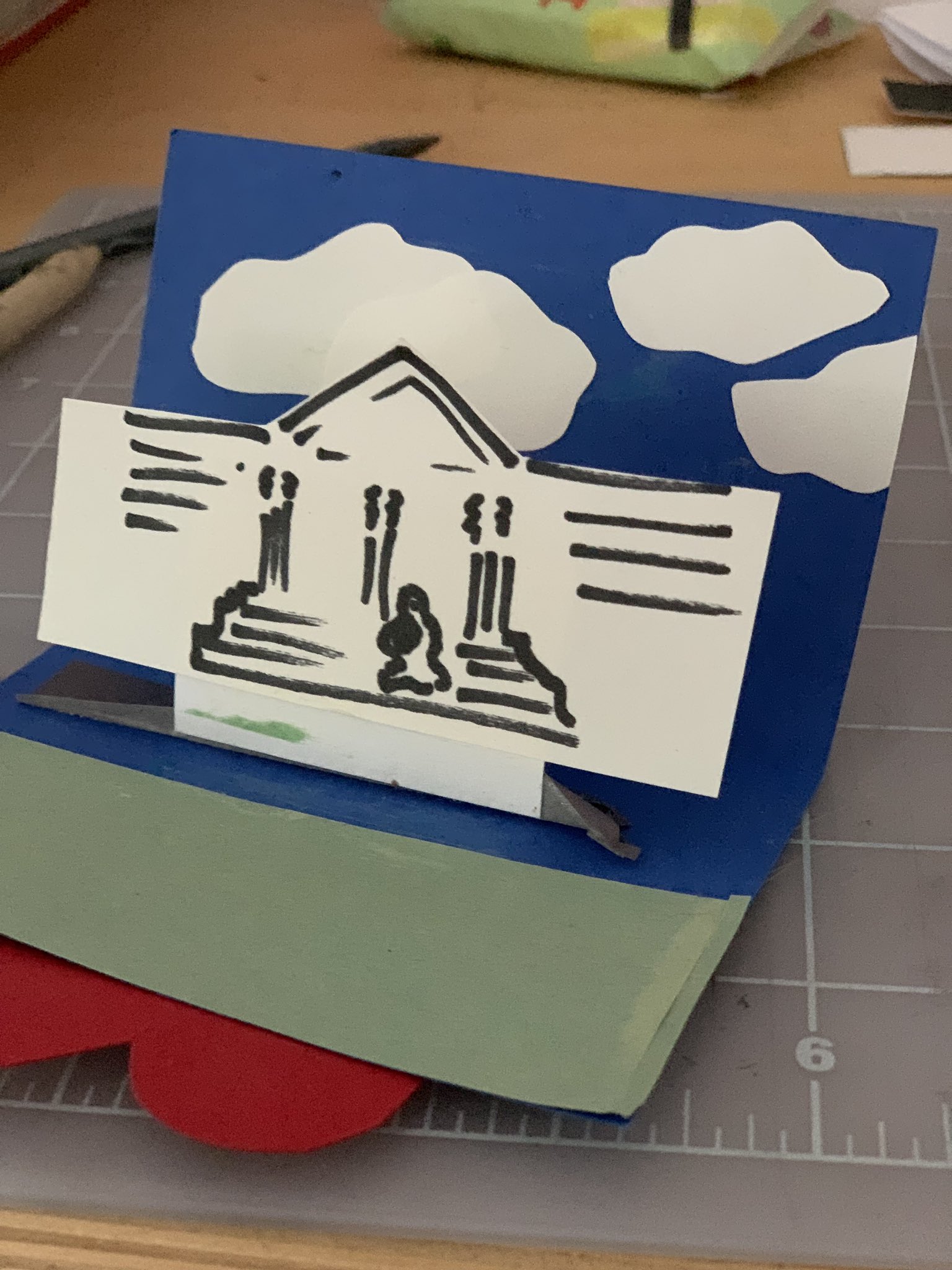

Also the picture at the header was my old desk, and it was part of Chad Weinard's wonderful talk about work from an age old MCN conference.