|

| The Ship of Fools by Hieronymus Bosch, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 |

By Seema Rao and Paul Bowers

I've been living in a wintery wonderland and luxuriating a beachy wonderland in equal turns recently. Last week, Rob Weisberg posted when I was at MCN (sadly as missing him terribly at that conference.)

I'm so glad to have gotten to go to MCN. Museum Computer Network has become my Shangri-la, in a way. A mirage, I see even when it's not there. I connect with many of those people online and in email. I wrote a bit about my true love for my conference friends last week on Medium. I wrote that post because I had one heck of a conference. So many things that had meant so much to me were coming to fruition, and like a godparent, I had barely anything to do with them. It felt great and also like an out of body experience.

In some ways, museum work has this illusory aspect. Or museum work is like atomic theory perhaps. We all have so many colleagues we rarely meet. And, then you run into each other in life or online, maybe exchange some energy, and like electrons bounce to higher levels.

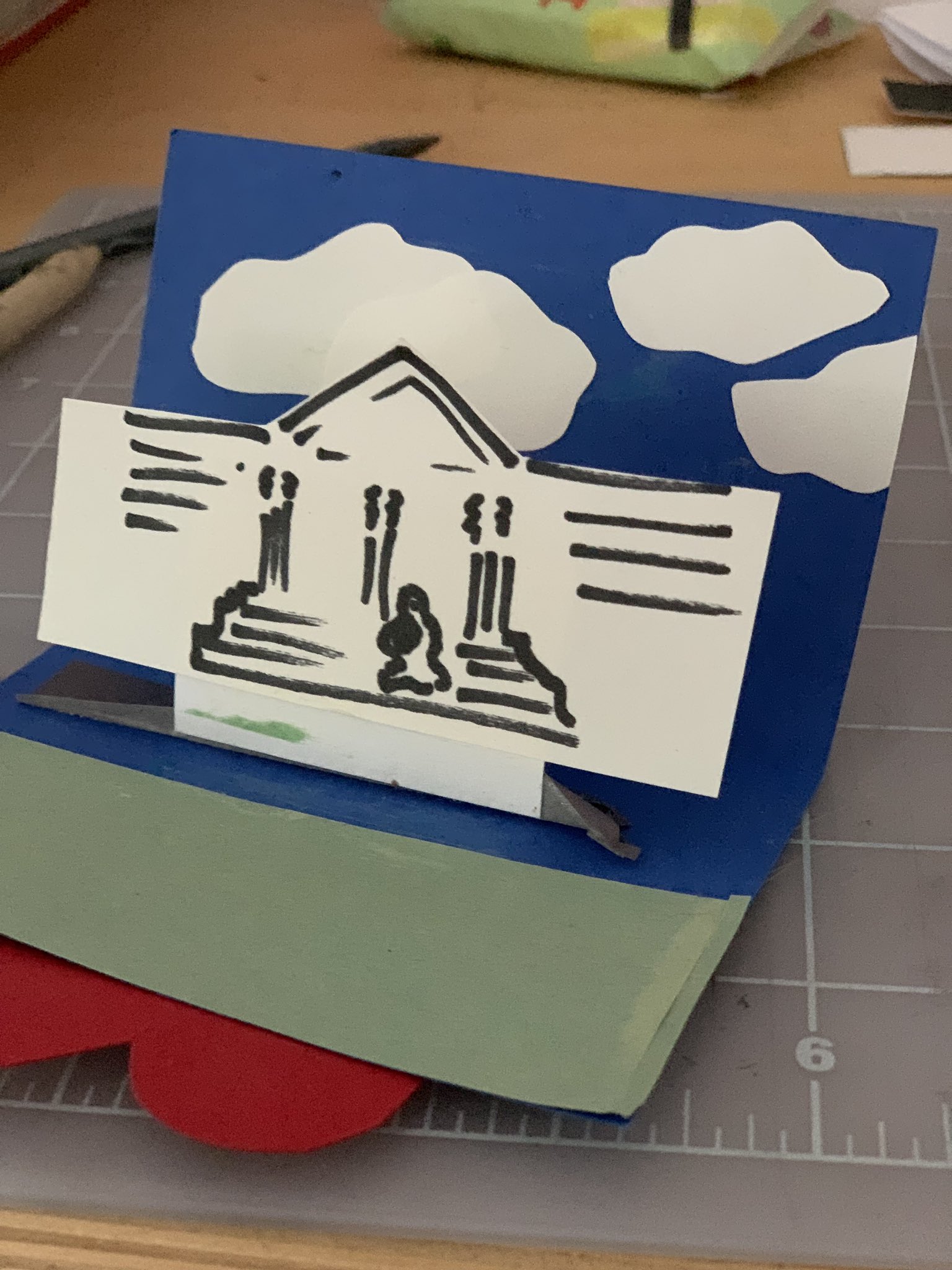

This idea of bouncing ideas and growing them might be said for my other post of the week, about touching art. I'm pretty open to a number of possibilities in museums. I am most definitely not open on the issues of collection care. The sanctity of the work is paramount. So how do we balance NO Touching policies and messaging against welcoming visitors? I don't have an answer, but would love to increase my energy levels on best solutions with your help. (as always drop by a line in comments or at Twitter @artlust) So in this case, I'm hoping you run into me with your ideas. (I did this illustration on my plane back from MCN that made me feel better though offered few solutions. And yes, it really is 2 Legit 2 Legit to quit. But I couldn't. I just couldn't).

All this meandering introduction, perhaps, is to lead up to this week's guest speaker. I've definitely felt energized by interacting with him, usually online. Paul lives in Australia, and I've had a couple of meals with him at most. I've also had very thoughtful conversations with him and I feel I've found a kindred spirit. So much so, we've presented a paper together on the stage of MuseumNext. I was thrilled he was willing to share some of his thoughts here today. Enjoy.

---

Are we one team?

By Paul Bowers

As Seema wrote in the first of the work series, our

sector has been professionalized and reshaped over the past few decades. While

we are enriched by the many professional fields intersecting to create the

contemporary museum workplace, it presents a challenge we rarely talk

about.

In every museum, we find different values, language and work

practices. I want a debrief, you talk about retros; I ask for the budget, you

offer me the ‘P and L’. A successful day for the retail team is not the same as

for the registrars - how do we work together when some people want to make a

profit, and others study provenance? Many workplaces have these complexities,

but I think our sector is unique in the sheer number of different domain

experts - and that means we have to work harder than most at building common

cause.

Lots of low-level workplace frustration can be laid at this

door. I think I could fund my coffee habit if I had a dollar for each complaint

of ‘Jeff from department blah is messing up my project, grrr.’ And there’s

always a Jeff to blame: I’m sure even Jeff has a Jeff.

Before offering some suggestions, it’s important to

emphasize there are a lot of unspoken assumptions of privilege and social

encoding around values and how things should be done: that ‘academic’ is

superior to ‘technical’, for example. We must be mindful, humble and open to

learn about the privilege we may have in the workplace.

That being said, my first suggestion is to slow down: invest

time in being clear what we mean and why we are acting as we are. Expertise

gleaned from years in one sector, understood easily with your department

colleagues, doesn’t automatically feel valid to someone without this

experience. Deploying authority to win is easy but doesn’t help in the long

run. We build trust and social capital by taking the time to explain - and

explaining our reasoning can often assist in clarifying our thinking.

Overt your values, rationale and motivations. When passing

on a piece of work, be clear, ‘I did it like this because _____.’ An exhibition

team of mine was in conflict with the functions and events team - it was

resolved when that department head said ‘I love doing two things at work:

making money and supporting the arts. When I make money, it pays for

exhibitions. That’s why I want to make more money.’ Written here, it looks

patronizing - but in that moment, the direct simplicity brought clarity and

drained conflict from the conversations.

My second suggestion is to remember that no-one comes to

work to do a terrible job or annoy their co-workers. So when someone seems

frustrating, work really hard at assuming good intent. Reflect on ‘how do they

think they are creating a positive impact in this conversation?’ Find a way to

ask - can you explain a bit more about how this way of working moves us

forward? Usually, there is an excellent reason!

The legal team in a previous museum frustrated me - they

were excruciatingly slow. And then a mutual colleague explained how it looked

from their perspective - slowing me down and checking the detail was their job,

to protect the organization against the existential threat of a huge legal cost

in the future. This helped me see their contribution as a positive thing.

My final suggestion is to be more intentional about purpose,

and who owns it. We can often unintentionally create micro-empires around tiny

tasks, rather than cohesive language around a shared endeavor. Stating ‘I will

select the artworks, you will prepare and document them, they will install

them’ may be factually accurate, but it is so much better to say ‘let’s work

together on getting this exhibition looking great, let’s agree how we’ll get it

done, how about this: …’ before that statement. Use collective language in

every situation, unless talking about your own direct accountability.

I’m sure there are many more ways to create and maintain

common cause with the different professionals who make up our workforce. The

goal isn’t to make everyone work the same - I’d be a terrible legal counsel! -

but if we can reduce friction and create more harmony, the rewards for us as

workers (including Jeff!), and eventually for our audiences, will be great.

Paul Bowers is a museum professional in Melbourne,

Australia, who usually blogs at